Chapter 02: The AdTech & Programmatic Advertising Landscape

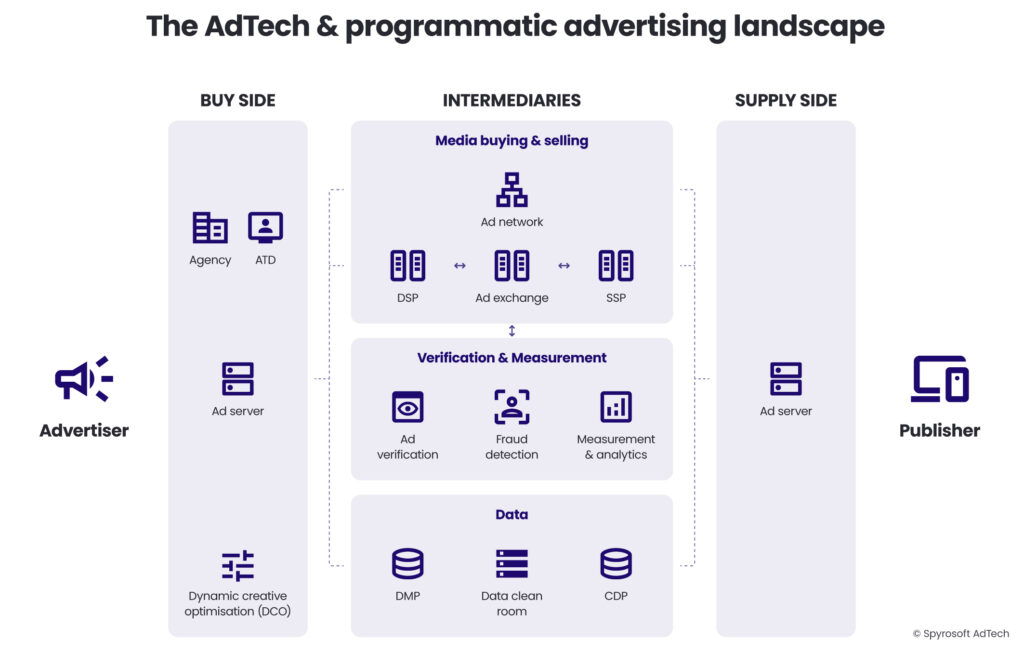

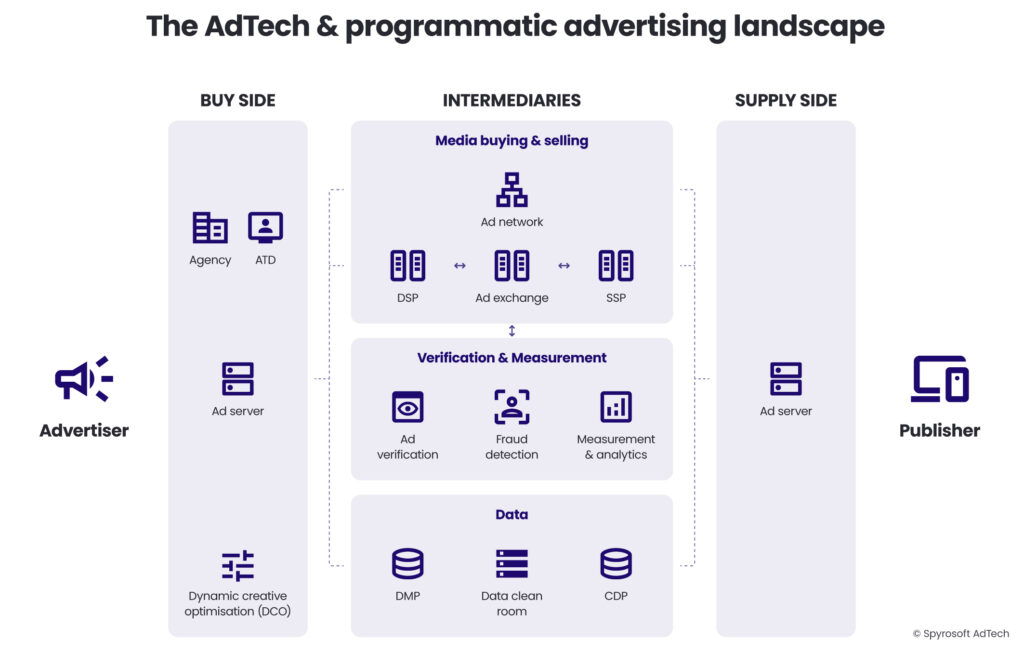

The digital advertising landscape consists of interconnected players, processes, and technologies designed to automate the buying and selling of digital advertising inventory.

At its core are advertisers and publishers, with numerous specialised platforms and agencies acting as intermediaries.

In this chapter, we’ll look at the key players in the programmatic advertising industry, the main processes, and the technological platforms that power them.

Key takeaways from this chapter

- Advertisers seek to promote their products or services to targeted audiences, while publishers aim to monetise their digital properties by creating or distributing content that attracts audiences.

- The key AdTech platforms include ad servers (for creative management and ad delivery), ad networks (for inventory aggregation), DSPs (for automated buying), SSPs (for publisher inventory management and automated selling), and ad exchanges (marketplaces for real-time bidding).

- The core programmatic processes include ad targeting (delivering relevant ads to specific users), frequency capping (preventing ad fatigue), and measurement & attribution (understanding campaign effectiveness).

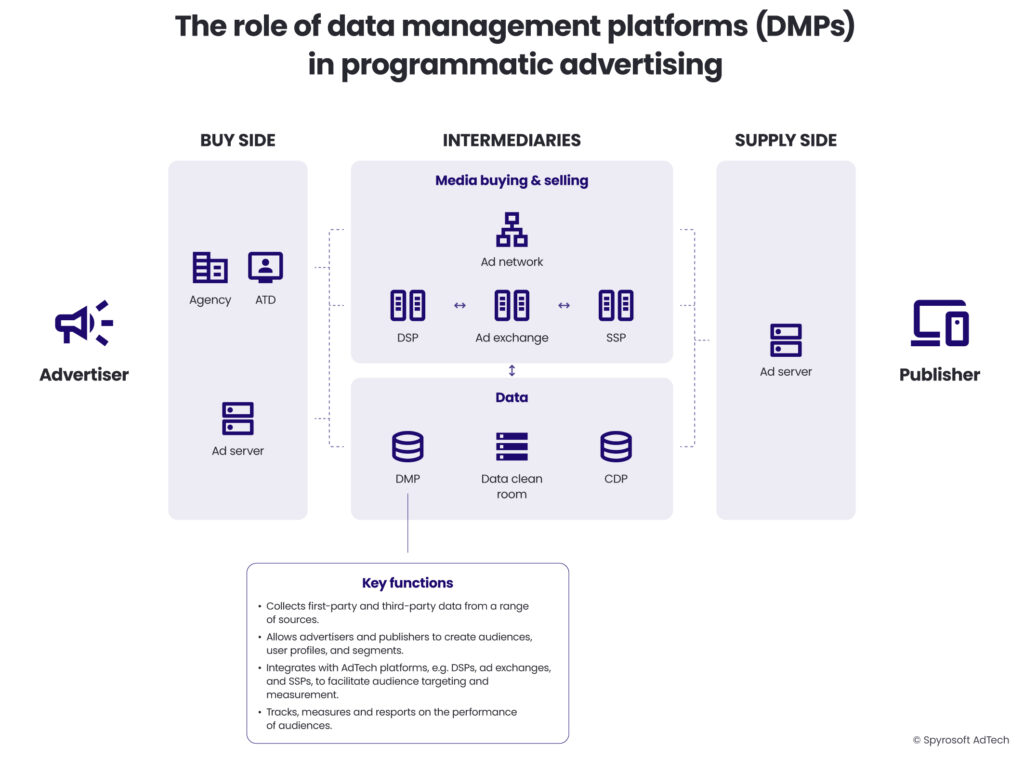

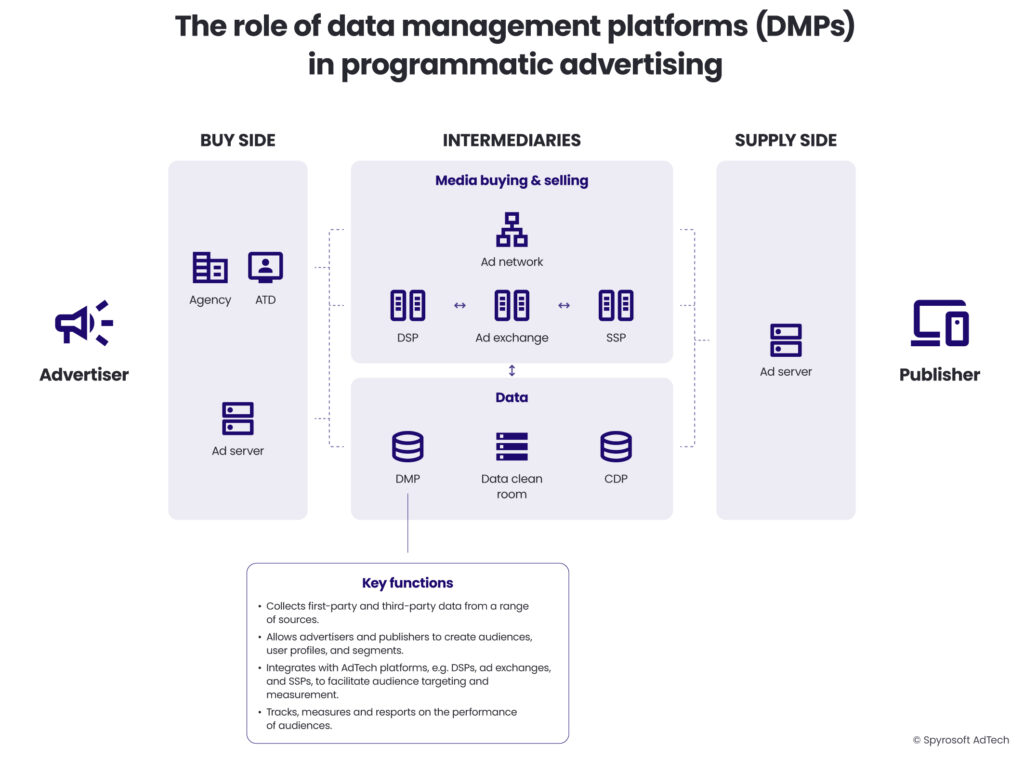

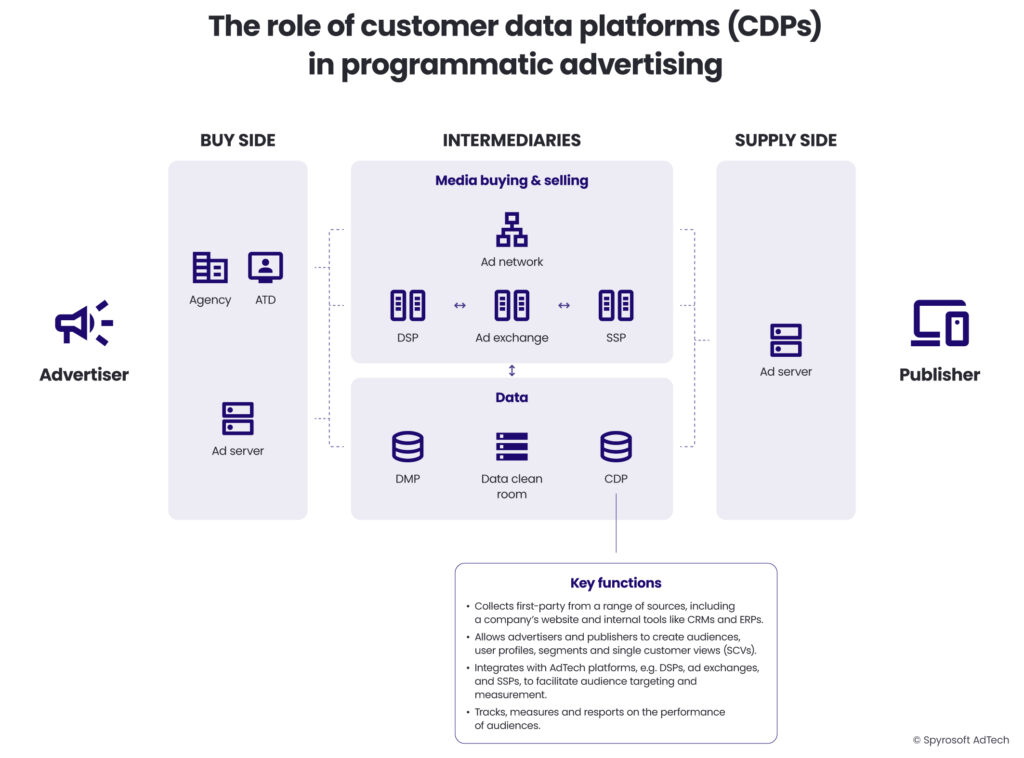

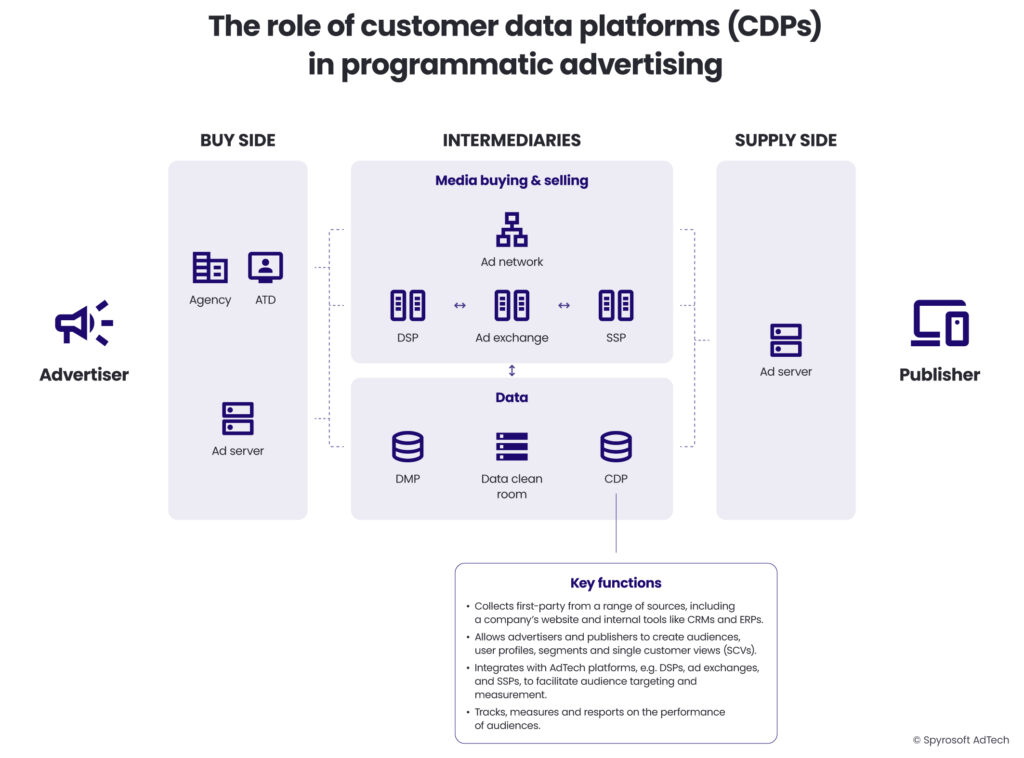

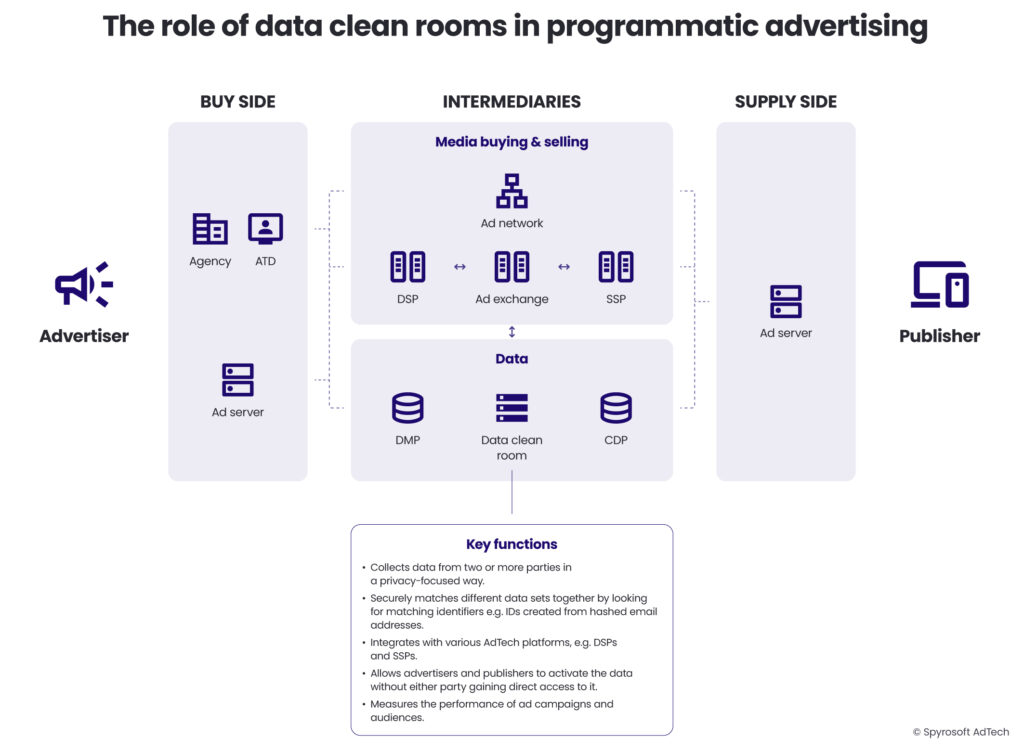

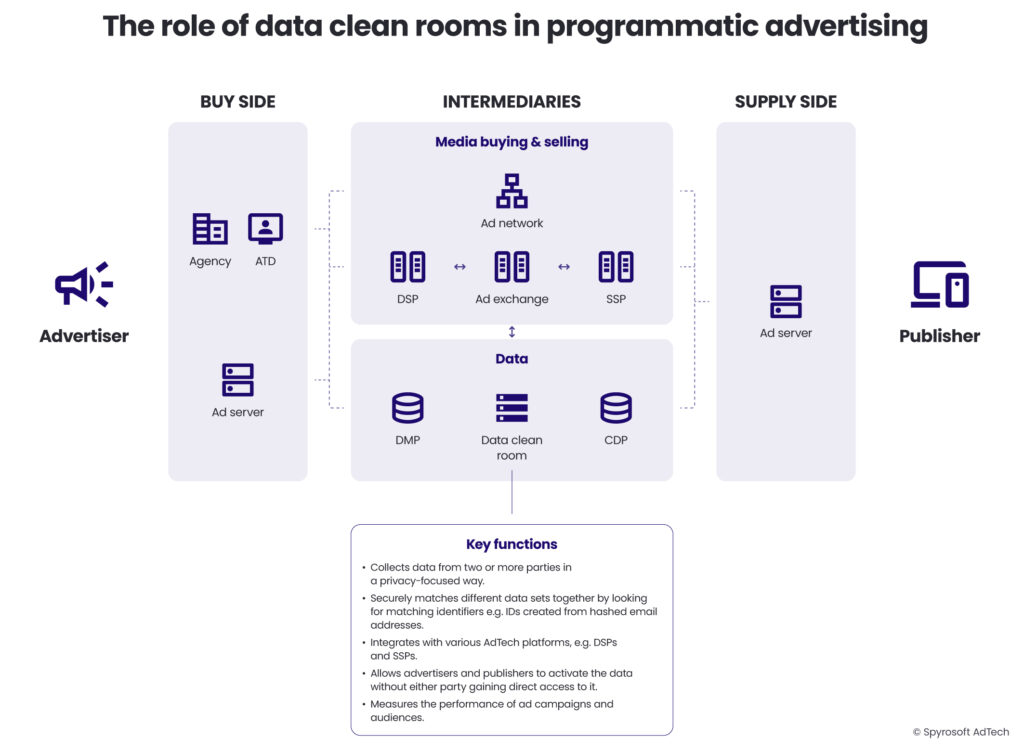

- Data management platforms (DMPs) and customer data platforms (CDPs) enable sophisticated audience targeting through data collection and segmentation, while data clean rooms enable privacy-safe collaboration between parties

- The AdTech ecosystem continues to evolve with increasing focus on first-party data, privacy compliance, and AI-driven optimisation.

Introduction

The digital advertising landscape, particularly in programmatic advertising, is a complex ecosystem made up of interconnected players, processes, and technologies.

At its core, this landscape is designed to automate the buying and selling of digital advertising inventory, enabling advertisers to efficiently reach their desired audiences and helping publishers effectively monetise their content.

In this ecosystem, advertisers and publishers represent the primary stakeholders.

However, several intermediaries and specialised platforms play critical roles, facilitating the smooth flow of data, ads, and revenue. Understanding each component—from the essential actors like advertisers and publishers to various technology platforms and intricate processes—is fundamental to grasping how the entire AdTech ecosystem functions.

The advertiser and the publisher

At the heart of the digital advertising ecosystem lie two main entities: advertisers and publishers.

Both have distinct yet interconnected roles, driven by the shared objective of exchanging value.

Advertisers

Advertisers represent brands, businesses, or individuals seeking to promote products, services, or messages to targeted audiences. The primary goal for advertisers is to achieve specific marketing objectives, such as brand awareness, lead generation, customer acquisition, or direct sales.

Advertisers typically set up campaigns defined by:

- Target audiences: Identifying demographics, interests, behaviours, or geographic locations.

- Budgets: Allocating funds to various advertising channels and platforms.

- Goals and metrics: Establishing performance indicators like click-through rates (CTR), conversion rates, return on ad spend (ROAS), or cost-per-acquisition (CPA).

Advertisers often collaborate closely with advertising agencies or in-house marketing teams to manage campaigns, optimise performance, and leverage data insights. They rely heavily on AdTech platforms such as demand-side platforms (DSPs) to access ad inventory programmatically, ensuring their ads reach the right audience efficiently.

Publishers

Publishers are content creators or owners—websites, blogs, mobile apps, video-streaming platforms, and other digital media outlets—that offer ad inventory, the available space designated for displaying ads. Their primary goal is to generate revenue by monetising their digital content effectively.

Publishers manage various forms of ad inventory, which might include:

- Display inventory: Ad spaces on web pages designed for banners, text, or image-based ads.

- Video inventory: Slots available for video ads before (pre-roll), during (mid-roll), or after (post-roll) video content.

- Native inventory: Ads that blend seamlessly with the website’s content.

To efficiently sell their inventory and maximise earnings, publishers typically use supply-side platforms (SSPs), ad exchanges, ad networks, or engage directly with advertisers. They leverage detailed analytics to measure ad performance, optimise inventory pricing, and reduce ad fraud.

The interaction between advertisers and publishers

The interaction between advertisers and publishers, often facilitated by various AdTech platforms, revolves around a continuous cycle of buying and selling digital ad inventory.

Programmatic advertising has significantly streamlined this interaction by automating the negotiation and transaction process through media-buying processes such as real-time bidding (RTB) and private marketplace deals, enabling greater efficiency, targeting precision, and measurable outcomes.

The role of advertising agencies

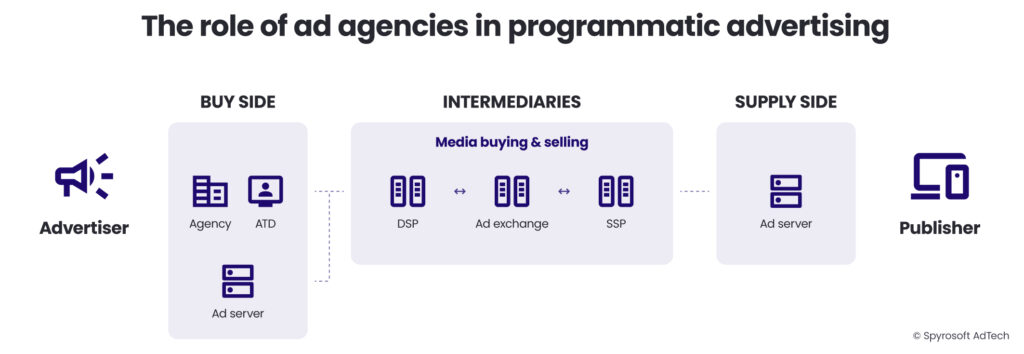

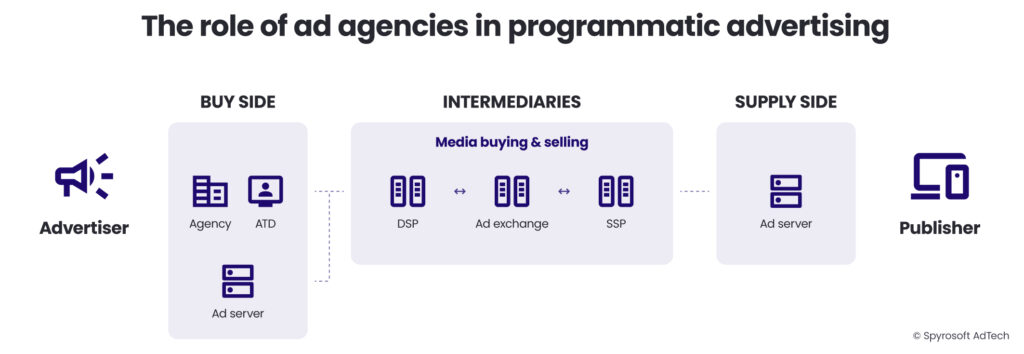

Advertising agencies act as intermediaries between advertisers and publishers, providing expertise, strategic guidance, and operational support in planning, executing, and optimising advertising campaigns.

Agencies vary significantly in size and scope, ranging from small agencies to large global holding companies.

Here are some of the most prominent ones:

Headquartered in Paris, France, Publicis has recently become the world’s largest advertising company, surpassing WPP. This achievement is attributed to strategic acquisitions and robust growth in digital marketing sectors.

Based in London, UK, WPP is a multinational communications, advertising, public relations, and technology holding company. It owns numerous agencies, including Ogilvy, Grey, and VMLY&R, and operates in over 100 countries.

Headquartered in New York City, USA, Omnicom is a global media, marketing, and corporate communications holding company. It comprises agency networks such as BBDO Worldwide, DDB Worldwide, and TBWA Worldwide.

Also based in New York City, IPG is a multinational advertising and public relations conglomerate. Its agencies include McCann Worldgroup and FCB. Notably, Omnicom has agreed to acquire IPG, which will create the world’s largest advertising agency with combined annual revenues nearing $26 billion.

A division of the French multinational Havas, Havas Creative operates 316 offices in 75 countries. It offers advertising, marketing, and corporate communications services and is recognised as one of the largest integrated marketing communications agencies globally.

Agencies generally offer services including:

- Strategic planning: Developing comprehensive media strategies tailored to an advertiser’s goals, target audience, and budget.

- Creative development: Crafting compelling ad creatives and messaging designed to engage and convert target audiences.

- Media buying: Negotiating and purchasing ad space across various digital and traditional channels to maximise reach and efficiency.

- Campaign management and optimisation: Continuously monitoring campaign performance, adjusting targeting, messaging, and placement to achieve optimal results.

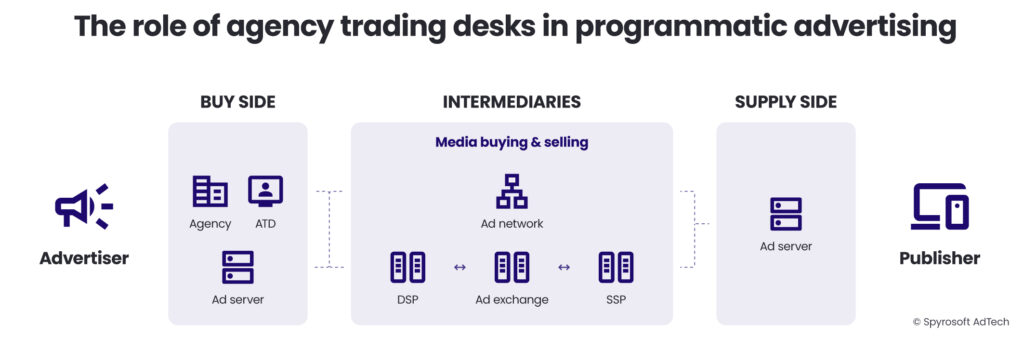

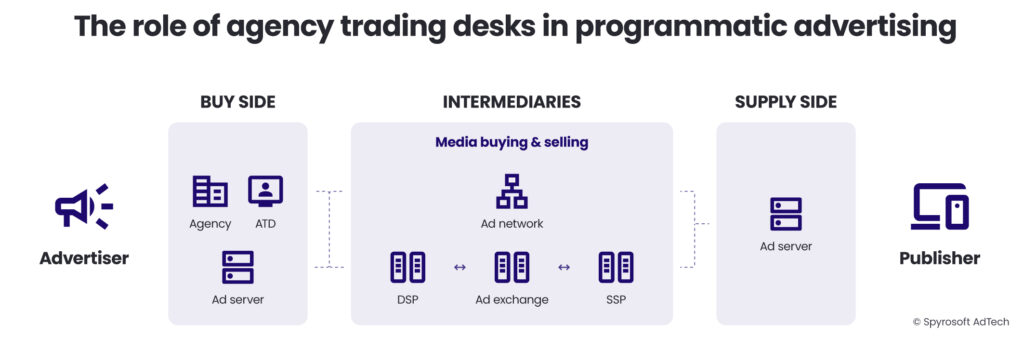

Many advertising agencies operate dedicated agency trading desks (ATDs)—specialised units focused on programmatic media buying through DSPs.

These trading desks use advanced algorithms, data-driven insights, and real-time optimisation to enhance advertising effectiveness and efficiency for their clients.

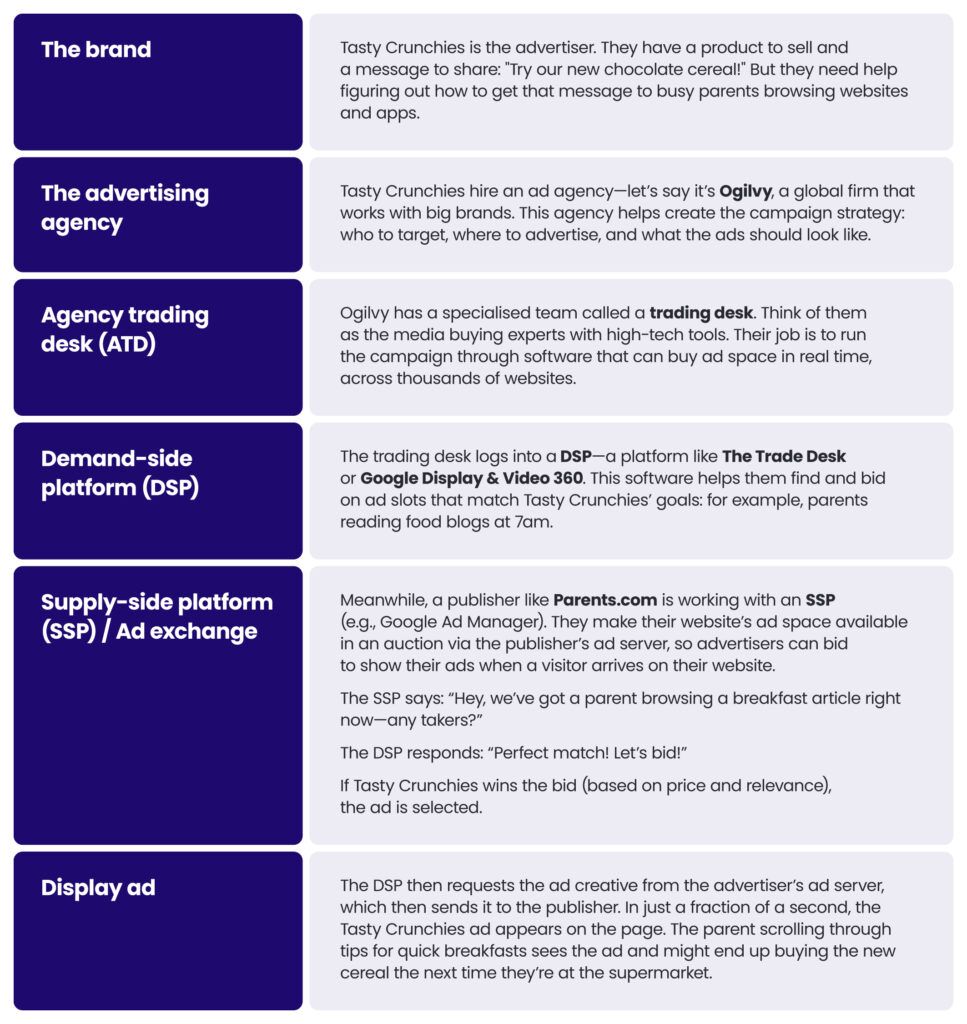

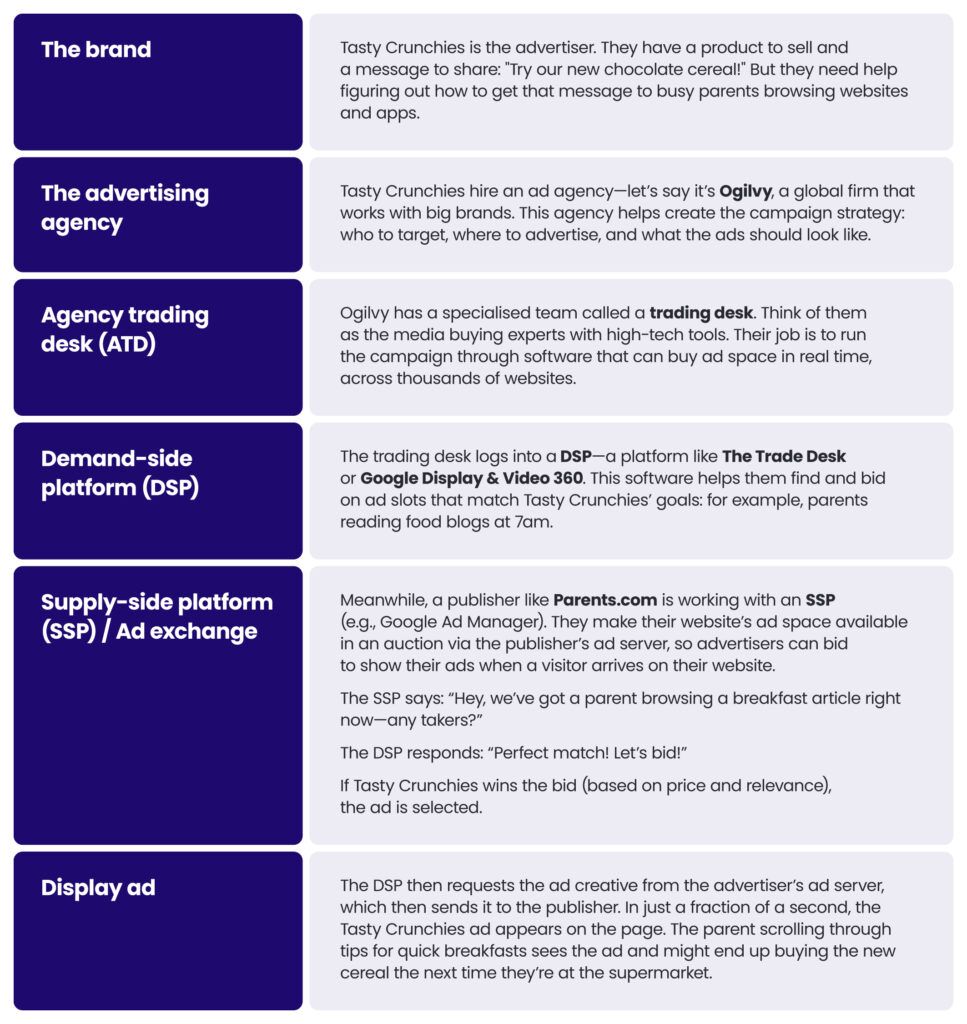

Let’s illustrate this with an example.

Imagine a cereal company—we’ll call them Tasty Crunchies–has just launched a new chocolate flavor and wants to spread the word to parents who shop online. Instead of calling every website one by one to place ads (like in the early internet days), they use programmatic advertising to get their ad onto the right screens, at the right time, automatically.

Let’s walk through the journey that ad takes.

The anatomy of an ad creative

Once an advertiser decides what they want to say and who they want to reach—and a publisher agrees to show the ad—the next step is figuring out where and how the ad appears.

That’s where the ad creative comes into play.

Just like a billboard needs space on a highway, a digital ad needs a place to live on a website or app—and it has to be designed to fit and function in that space.

To understand how advertisers and publishers coordinate this, we need to unpack the core elements that make up every digital ad placement.

Ad space

This is the part of a web page or app screen reserved for advertising, such as the banner at the top of a news article or a sponsored tile in a mobile game.

Publishers decide where this space will be, how big it is, and how it behaves (e.g., scrollable, sticky, fullscreen).

Think of it like a billboard on a webpage—positioned to catch the user’s eye.

Ad slot

An ad slot refers to a specific instance of ad space on a page at a given time. It’s the technical container into which an ad is delivered. A single web page may have multiple ad slots—each with its own identifier and characteristics.

Example: A webpage might have three ad slots—one leaderboard at the top, one sidebar square, and one mid-article display unit.

Think of ad space as the location, and an ad slot as the parking spot available at that location during a specific moment. So, while ad space is the general area made available for ads on a website, an ad slot is the actual opportunity to show an ad to a specific person, at a specific time, in a specific space.

Premium, remnant and long-tail inventory

In digital advertising, inventory is the collective term for all the ad slots a publisher has available to sell. It includes all the potential impressions (views) a website or app can deliver over time.

Publishers often divide their inventory into:

- Premium inventory: Highly visible placements on high-traffic pages (e.g., homepage takeovers).

- Remnant inventory: Lower-priority slots or leftover impressions sold through automated auctions.

Example: A major news site may offer thousands of ad slots per hour—that’s their inventory.

Not all inventory comes from big-name publishers.

In fact, a huge portion of available ad space comes from the long tail—a term that refers to the countless smaller websites, blogs, forums, mobile apps, and niche content platforms that individually have modest traffic, but collectively represent the vast majority of available ad impressions.

Long-tail inventory plays a crucial role in programmatic advertising because:

- It offers massive scale at relatively low cost.

- It enables highly specific audience targeting, especially in niche communities.

- It provides cost-efficient performance marketing opportunities, ideal for retargeting and direct-response ads.

These smaller publishers use the same supply-side technology as larger ones (e.g., SSPs and ad networks), making their ad slots available in real-time bidding auctions.

To the DSP, a long-tail placement looks much the same as a premium one—what matters is the audience and context.

Creative

Once an ad slot is won, it needs content to fill it—that’s the creative.

In digital advertising, the term creative refers to the actual ad unit that gets displayed to the end user. It’s what you see on the screen: a video, a banner, an animated graphic, or even a native ad that blends into the content around it.

Display ads = the ad format/type (what’s bought and seen).

Display creatives = the creative files or variations used within display ad placements. The terms display ads and display creatives are often used interchangeably. Specifically, people often use “ads” as a catch-all term, even though it technically includes both the creative asset and the delivery mechanism.

Creatives are built to match the specifications of the ad slots they’re intended for, and must comply with a range of standards, formats, and technical requirements.

Let’s explore the key types of creatives and how they’re structured.

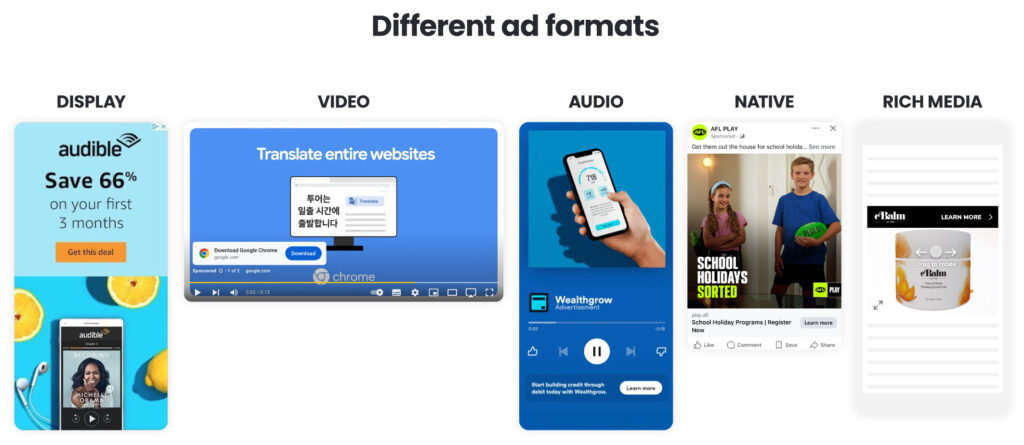

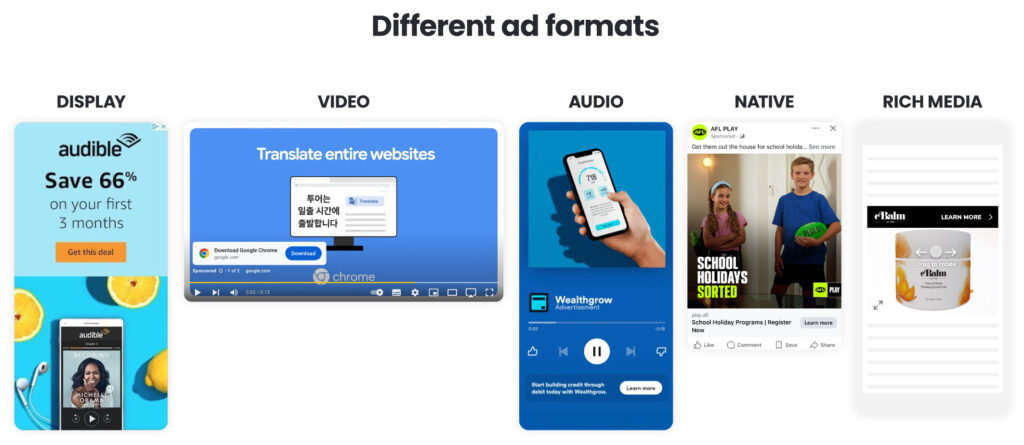

Display ads

Display creatives are image- or animation-based ads that appear in standard sizes across websites and apps. They’re the backbone of digital advertising and are among the most commonly served creatives.

Video ads

Video creatives are short video clips that can appear before (pre-roll), during (mid-roll), or after (post-roll) video content, or as standalone units in social feeds or outstream placements.

Audio ads

Audio creatives are used in streaming platforms (like Spotify, Pandora, or podcast networks) and target users in a sound-first context.

Native ads

Native creatives are designed to match the form and function of the surrounding content. Instead of standing out like a traditional banner, they blend in—appearing as recommended articles, sponsored posts, or product listings.

Rich media & interactive ads

These are advanced creatives that include interactivity, animations, videos, carousels, or gamified elements.

Dynamic creatives (DCO)

Dynamic creatives are automatically personalised at the time of impression. These ads use real-time data (e.g. location, browsing behaviour, weather) to generate tailored content on the fly.

Example: An ad for Nike shoes might show:

- Different models to different users

- Local pricing and store availability

- Weather-specific messaging (e.g. “Stay dry this fall with Gore-Tex”)

IAB and ad standardisation

The Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) is one of the most influential organisations in the digital advertising industry.

It sets the standards that make large-scale, automated advertising not only possible but consistent, reliable, and measurable.

Think of the IAB as the global referee and architect of digital advertising—it doesn’t run the game, but it writes the rules so that everyone plays fair and uses the same playbook.

For advertisers, publishers, and technology platforms, the IAB provides a shared foundation. Without it, the ecosystem would be fragmented, with every ad looking and behaving differently across platforms, screens, and websites.

Setting the standard for ad sizes and formats

One of the IAB’s most well-known contributions is its Standard Ad Unit Portfolio, which defines the size and format of display ads. This standardisation ensures that advertisers can design creatives that reliably fit into the spaces publishers provide.

When an ad is labeled as “IAB-compliant,” it means that it adheres to these specifications and is ready to be served across the programmatic landscape.

For instance, a 300×250 “medium rectangle” or a 728×90 “leaderboard” is instantly recognisable to anyone working in display advertising.

These are part of the IAB’s official specifications and are widely adopted across the globe. Because of these common sizes, a creative designed for one publisher can be reused across hundreds or thousands of websites and apps without needing custom resizing or reformatting.

Here are a few commonly used IAB-standard display ad sizes:

- 300×250 – Medium Rectangle

- 728×90 – Leaderboard

- 160×600 – Wide Skyscraper

- 300×600 – Half Page

- 320×50 – Mobile Leaderboard

- 970×250 – Billboard

These sizes are optimised for different screen types, contexts, and user experiences—from mobile apps to desktop news portals. They form the visual language of digital advertising, making creative production and placement scalable and efficient.

When advertisers and publishers talk about standard display sizes—like 300×250 (medium rectangle) or 728×90 (leaderboard)—they’re usually referring to formats defined by the IAB.

These formats are:

- Universally accepted by major publishers, ad exchanges, and DSPs.

- Designed for interoperability across devices and platforms.

- Supported by ad servers like Google Ad Manager, Xandr, and Adform.

- Built to ensure that creative content renders properly, regardless of environment.

Because they follow the same technical blueprint, IAB-standard formats make it easy for advertisers to scale campaigns efficiently across thousands of websites and apps in the open programmatic ecosystem.

Example: A 300×250 HTML5 banner created for one site can be reused across multiple news sites, gaming apps, and blog networks—all because those environments adhere to the same IAB specifications.

The IAB is constantly updating its ad sizes and formats to meet the ever-changing digital advertising channels and mediums.

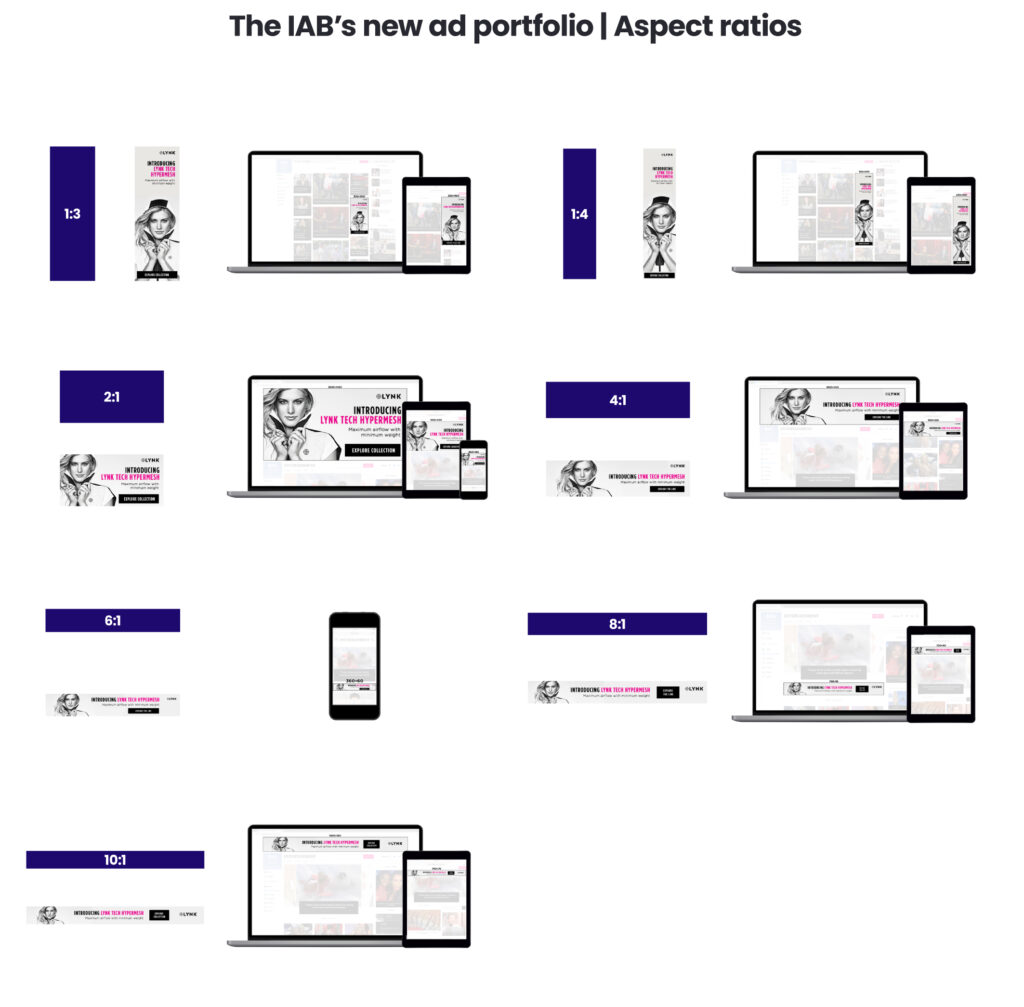

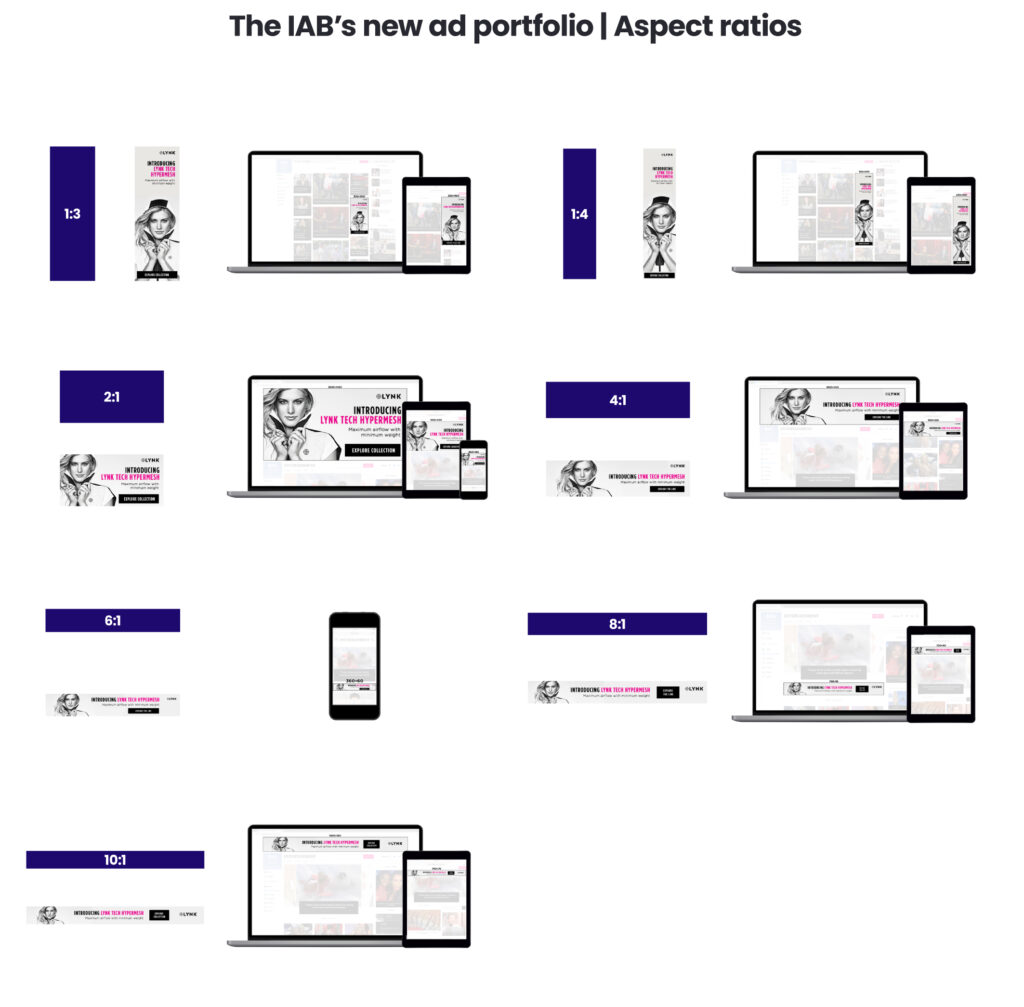

In February 2024, the IAB released its New Ad Portfolio to replace its previous creative display guidelines, including the Universal Ad Package (UAP) and rich media units.

These new ad formats are based on aspect ratios instead of fixed pixel sizes.

Below are some of the common aspect ratios in the New Ad Portfolio guidelines.

More than just sizes: technical and measurement standards

While ad sizes are the most visible part of the IAB’s work, the organisation’s influence runs much deeper.

Through its technical arm, the IAB Tech Lab, it has introduced and maintained many of the foundational protocols that power programmatic advertising behind the scenes.

Some of the IAB Tech Lab’s main standards and protocols include:

- VAST (Video Ad Serving Template) ensures that video ads can be delivered to video players across different platforms.

- OpenRTB (Open Real-Time Bidding) creates a common language for buying and selling ads in real time.

- The OMSDK (Open Measurement SDK) provides standardised ways to verify whether an ad was viewable.

- MRAID (Mobile Rich Media Ad Interface Definitions) governs how interactive mobile ads function within apps.

These standards do more than facilitate delivery—they ensure that ads are measurable, viewable, and compatible across platforms, from mobile apps to smart TVs. They also create the foundation for trust and transparency between buyers and sellers.

Why the IAB matters

In a programmatic world where billions of ads are transacted and served every day, consistency is critical.

Without the IAB and its standards, advertisers would struggle to scale campaigns across the open internet, and publishers would face overwhelming complexity in integrating different ad technologies.

By defining the specs for both creatives and the technical systems that deliver them, the IAB makes interoperability possible. It ensures that an ad designed in one part of the world can be served, measured, and monetised in another—with confidence that it will render correctly and meet industry expectations.

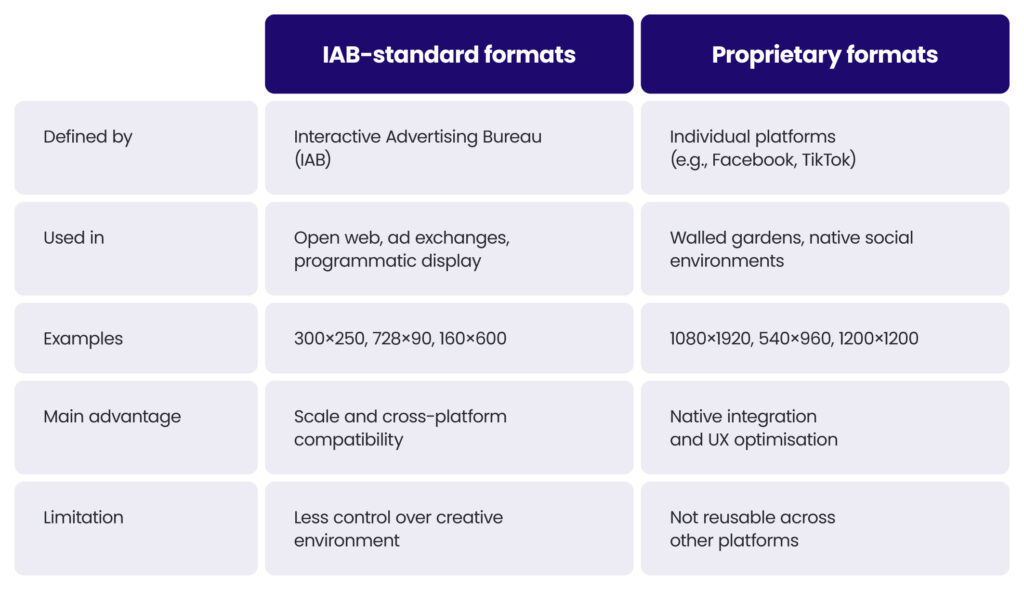

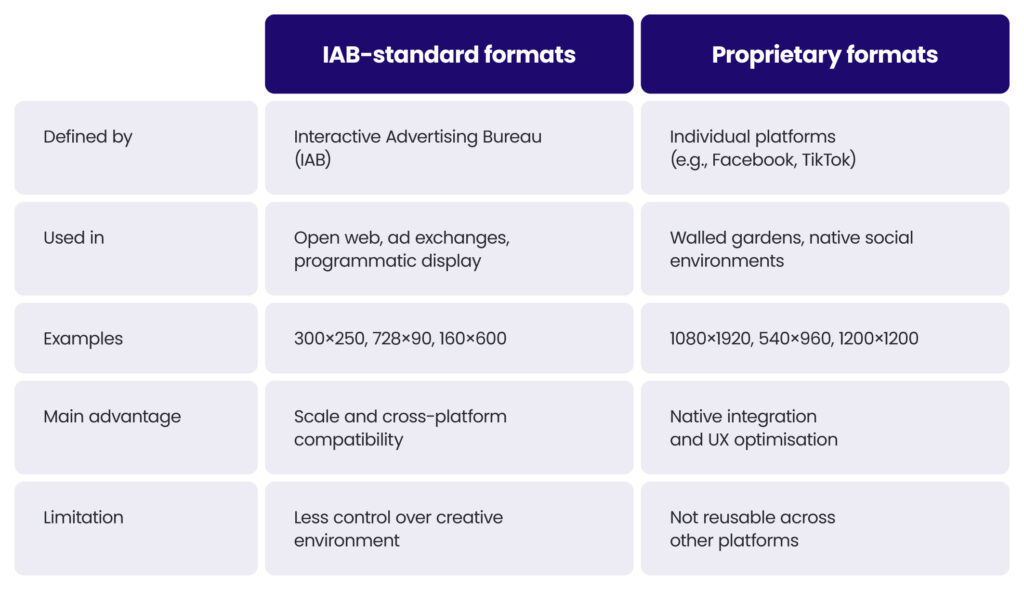

Proprietary ad formats: The walled garden approach

While the open web depends on shared standards, social media platforms and other closed ecosystems—often referred to as walled gardens—create and enforce their own specifications.

Platforms like Meta (Facebook & Instagram), TikTok, Snapchat, and X (formerly Twitter) define their own ad sizes, durations, and behaviours based on how content appears in their unique user experiences.

These proprietary formats are tightly integrated into their platforms and not intended to be interoperable with external systems.

For example:

- Facebook stories require a 1080×1920 vertical image or video

- TikTok’s top-view ads use a 540×960 video format

- Twitter carousels may be 1200×1200 square or 628×1200 vertical

Each format is optimised for the platform’s feed layout, user interface, and engagement style.

For example, an ad designed for Instagram Stories won’t automatically work in Google Display ads or in a mobile news app – it must be built to match Instagram’s own creative and performance guidelines.

That’s why most large-scale campaigns use both IAB-compliant creatives for open web inventory via programmatic channels and platform-specific assets tailored to each social media environment.

For advertisers, navigating these dual standards requires thoughtful planning during creative development and media buying:

- Design assets in multiple sizes and formats from the start.

- Use dynamic creative optimisation (DCO) tools to manage versioning across environments.

- Ensure ad servers and DSPs can handle both IAB-compliant and custom formats.

- Align performance goals with each format’s strengths (e.g., native engagement vs. broad reach).

Bringing it all together

Here’s how it works in context:

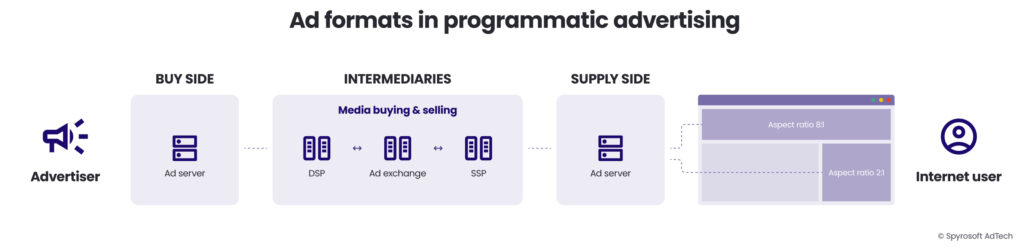

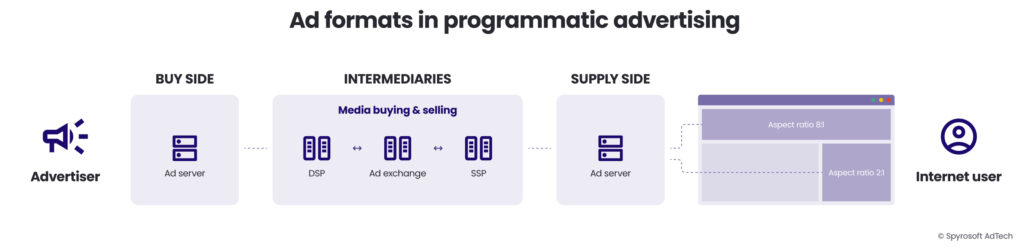

- A user visits a lifestyle blog. The page loads and triggers two ad slots. One of those is a leaderboard ad slot at the top with an aspect ratio of 8:1 and the other is an ad with an aspect ratio of 2:1.

- The blog’s ad server selects its supply-side platform (SSP), which then sends out a bid request for that ad slot. The request is sent to an ad exchange and an auction is held. A DSP on the advertiser’s side wins the auction.

- The DSP sends a request to the advertiser’s ad server to retrieve the ad creative and serve into that ad slot.

The main AdTech platforms and their role

As digital advertising evolved from simple banner ads to a multi-billion-dollar programmatic ecosystem, one thing became clear: no single tool or company could manage everything.

A constellation of specialised platforms emerged very soon, each designed to solve a specific challenge in the advertising supply chain – from serving creatives and targeting audiences to optimising performance and protecting user data.

Understanding these platforms and how they interact is essential to making sense of the AdTech landscape.

Let’s review how each of these platforms came to be, what role it plays, and how it connects to the others.

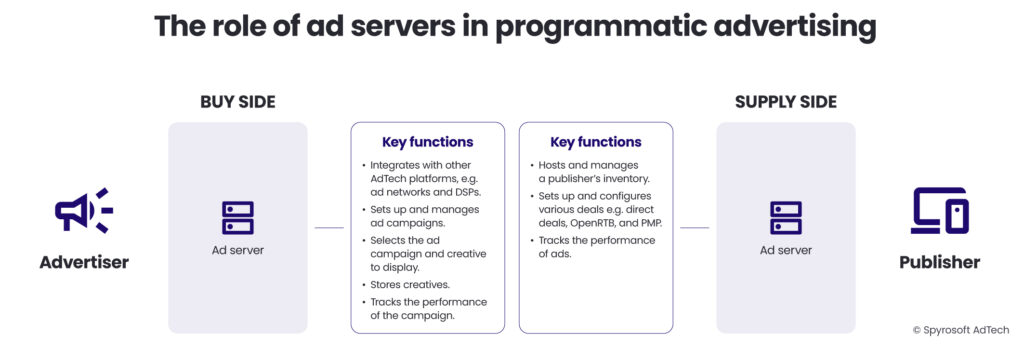

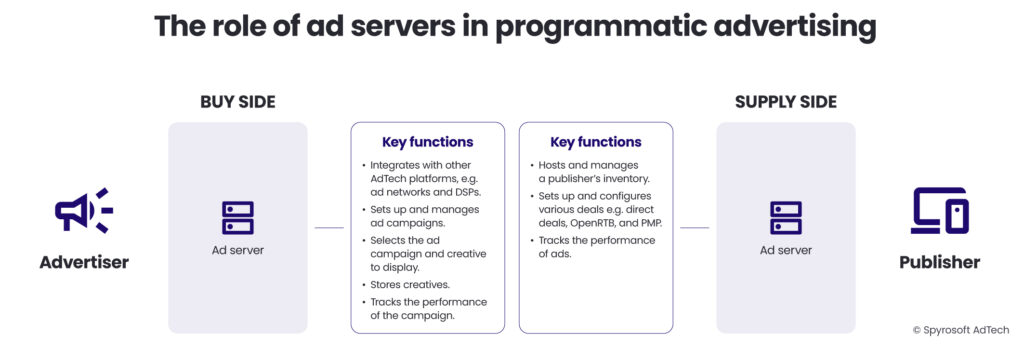

Ad servers

An ad server is a piece of software that is responsible for making decisions about which campaigns to run, which ads to show, and measuring the performance of advertising campaigns.

They are a key piece of the AdTech stack and integrate with other AdTech platforms, such as demand-side platforms (DSPs), supply-side platforms (SSPs), and ad networks, to facilitate the automated buying, selling, delivery, and measurement of digital advertising.

They are used by both advertisers and publishers.

An advertiser’s ad server, also known as a third-party ad server, is responsible for:

- Setting up ad campaigns for various digital advertising channels, e.g. display and in-app mobile.

- Deciding which ad campaign to run based on the information passed to it from another AdTech platform, e.g. a publisher’s ad server.

- Tracking individual impressions across the web and reporting on their performance, e.g. counting the number of views and clicks they receive.

A publisher’s ad server, also known as a first-party ad server, is responsible for:

- Hosting and managing a publisher’s ad inventory.

- Setting up and configuring a publisher’s various deal types, e.g. direct deals, open RTB and PMP deals, and programmatic guaranteed deals.

- Managing a publisher’s waterfall and header bidding setups.

- Tracking the performance of ads, such as impressions and clicks.

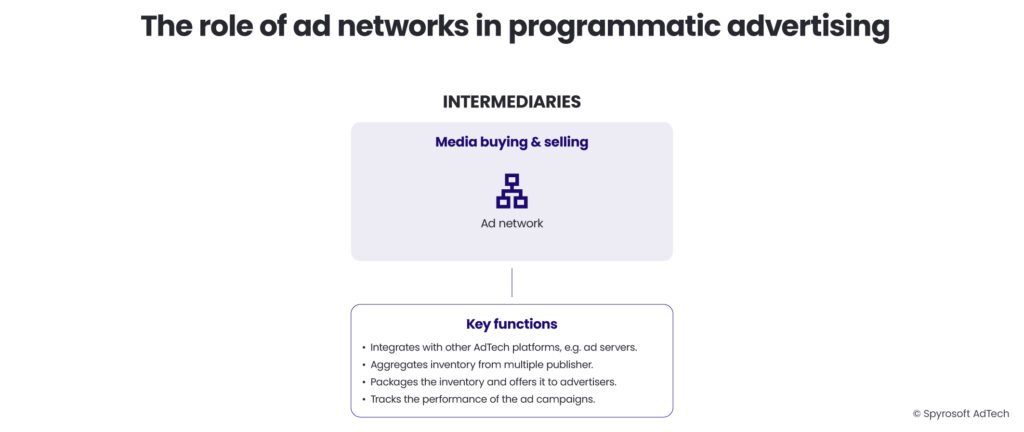

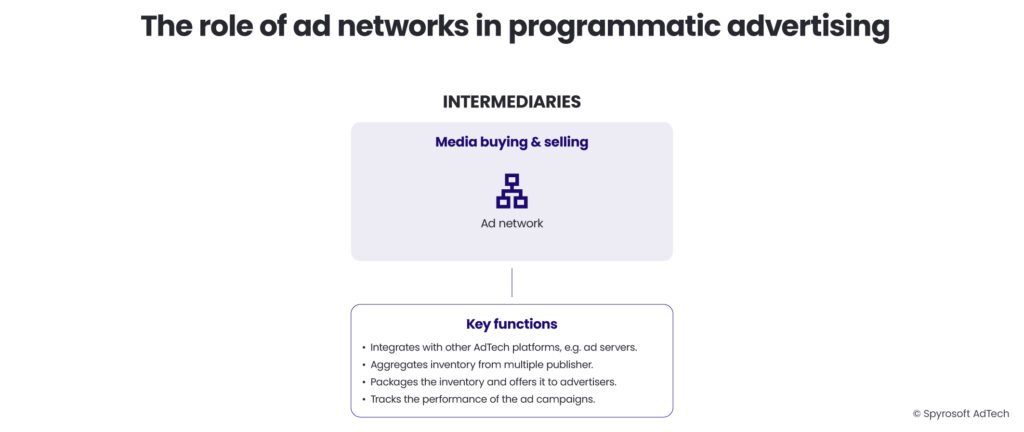

Ad networks

An ad network is a piece of advertising software that facilitates the buying and selling of aggregated digital inventory.

Think of ad networks as wholesalers in the digital ad supply chain. They make it easy for advertisers to reach large audiences and help publishers monetise leftover (remnant) inventory.

Ad networks do this by collecting ad inventory from multiple publishers, sometimes thousands, and selling it to advertisers in bulk, e.g. on a cost per mille (CPM) basis.

The benefit of this is that advertisers get access to a defined audience at scale, whereas for publishers, they’re able to sell ad inventory that may not have sold via direct deals.

Popular ad networks include Google Adsense, Adcash, and Infolinks.

Though their dominance waned over the years, ad networks are starting to have a resurgence in popularity due to the rise of new digital channels like retail media and connected TV. Many retailers and video-streaming services are launching advertising businesses and are essentially operating an ad network model.

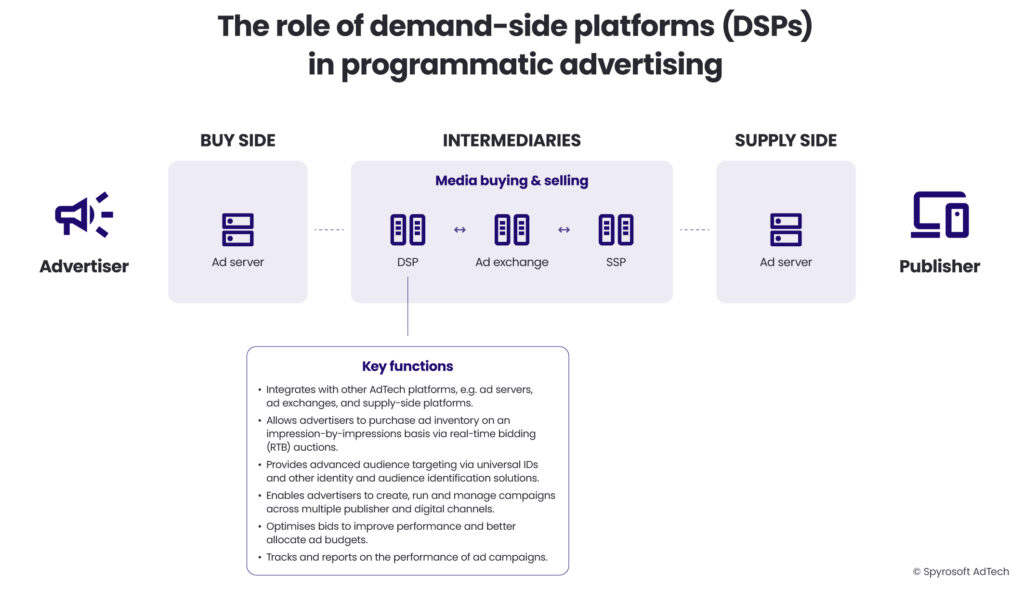

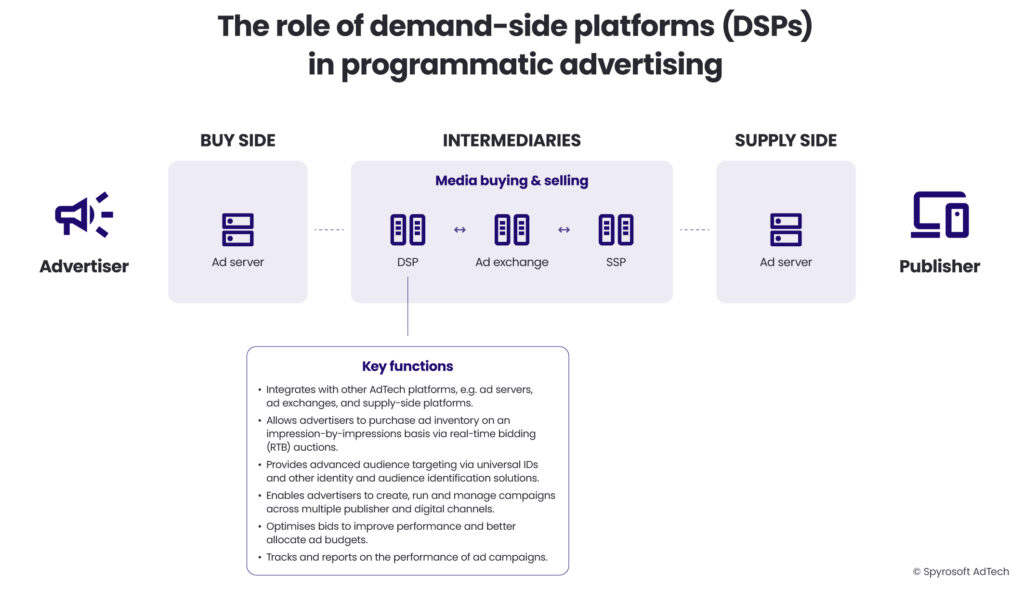

Demand-side platforms (DSPs): Automation for advertisers

The introduction of real-time bidding (RTB) in the late 2000s sparked yet again another round of technological innovation. On the buy side, a new AdTech platform emerged: a demand-side platform (DSP).

A DSP is an advertising platform that allows advertisers to buy digital ad inventory via the real-time bidding (RTB) process, across multiple publishers, supply-side platforms (SSPs), and ad exchanges.

It automates the entire buying process—from defining audience segments and setting bid prices to selecting creatives and tracking results.

A DSP combines the functions needed to plan, buy, and optimise digital ad campaigns programmatically.

What makes DSPs so powerful is not just the scale they offer, but the intelligence they enable. Modern DSPs integrate with data management platforms (DMPs), customer data platforms (CDPs), and dynamic creative tools to make every impression as targeted—and as effective—as possible.Some of the most widely used DSPs today include The Trade Desk, Google Display & Video 360, and Amazon DSP.

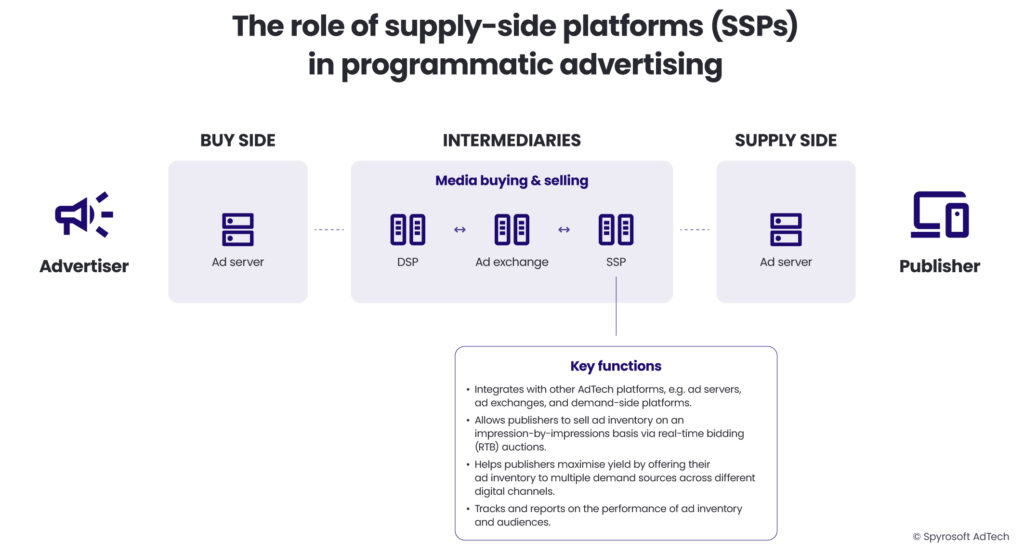

Supply-side platforms (SSPs)

As publishers demanded more control and transparency, supply-side platforms (SSPs) emerged. SSPs are platforms that allow publishers to manage, price, and sell their ad inventory programmatically.

Unlike ad networks, SSPs enable real-time auctions—meaning they can sell each impression to the highest bidder at the moment a user visits the page. This transformed how publishers made money, introducing dynamic pricing instead of static deals.

SSPs connect directly to ad exchanges, where inventory is offered to multiple demand-side platforms (DSPs) simultaneously. This increases competition for each impression, improving yield.

Examples of SSPs include Google Ad Manager (formerly DoubleClick for Publishers), Magnite, and PubMatic.

An SSP combines all the functions publishers need to sell and manage their digital inventory in real time.

DSPs vs SSPs

Despite serving opposite sides of the digital advertising marketplace, DSPs and SSPs share critical functional overlaps that enable the programmatic ecosystem to operate in real time.

Both platforms participate in real-time bidding (RTB)—SSPs initiate auctions by sending bid requests, while DSPs evaluate and respond with bids.

Each also leverages audience data to improve decision-making: DSPs use it for precise targeting, while SSPs use it for supply segmentation and prioritisation.

Additionally, both platforms rely on optimisation algorithms—SSPs aim to maximise yield for publishers, while DSPs strive to deliver cost-efficient results for advertisers.

Finally, both offer increasingly sophisticated reporting and analytics, with growing focus on transparency, reconciliation, and bidstream integrity. These shared capabilities create a seamless, data-driven bridge between buyers and sellers in the programmatic supply chain.

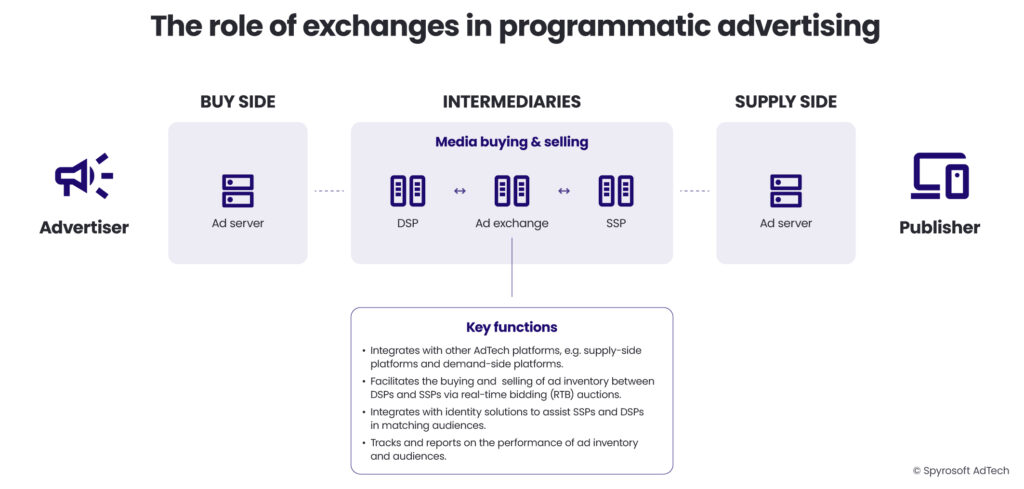

Ad exchanges

An ad exchange is the digital equivalent of a stock market for ads. It connects SSPs (representing publishers) with DSPs (representing advertisers) to facilitate real-time bidding (RTB) for individual ad impressions.

When a user loads a web page, the SSP sends a bid request to the exchange, which then invites multiple DSPs to place bids. The highest bidder wins, and the winning ad is served—usually in under 100 milliseconds.

The launch of exchanges like Right Media (acquired by Yahoo) and Google’s AdX marked the birth of real-time bidding (RTB).

Popular ad exchanges and SSPs include Google Ad Manager, Magnite, OpenX, PubMatic, and Index Exchange.

Supply-side platforms (SSPs), DSPs and ad exchanges are often used in the same context, but they serve distinct roles.

The table below outlines their key differences:

Agency trading desks (ATDs): Power tools for big brands

As DSPs gained traction, large media agencies began creating agency trading desks – in-house programmatic buying units that operated DSPs on behalf of clients.

These teams combined data science, media planning, and algorithmic buying under one roof.

ATDs enabled brands to centralise spend, standardise campaign execution, and extract better performance across fragmented media.

However, they also introduced concerns around data ownership, markup transparency, and conflicts of interest—especially when agencies prioritised deals that benefited their own bottom line.📌 Today, the ATD model is less visible as a standalone unit, but the functions they pioneered still matter. In fact, many have evolved into more holistic agency offerings focused on data, identity, and automation.

Data management platforms (DMPs)

As programmatic campaigns scaled, advertisers needed better ways to target the right users. That’s where data management platforms (DMPs) came in.

DMPs ingest and organise vast amounts of data—first-party, second-party, and third-party—to create targetable audience segments.

For instance, a DMP might group users who visited a car comparison site, added a product to a cart, or watched a video ad. These segments are then passed to DSPs for targeting.

DMPs helped move digital advertising beyond simple contextual or demographic targeting into behavioural and intent-based strategies. Popular platforms include Lotame, LiveRamp, and Adobe Audience Manager.

DMPs once served as the key data platform for programmatic advertising, particularly in a world reliant on third-party cookies.

But as privacy concerns mounted and regulations like GDPR and CCPA reshaped how data could be collected and used, the limitations of traditional DMPs became clear:

- They rely heavily on third-party cookies, which have been deprecated by major browsers like Firefox and Safari.

- They typically don’t collect a person’s name or email address, making them less suitable for long-term customer relationships.

- Their segmentation is often static or rule-based, lacking the real-time agility offered by newer platforms like CDPs.

As a result, many advertisers have started to shift toward customer data platforms (CDPs) for identity resolution and customer journey management, especially for owned audiences. That said, DMPs still play an important role in the upper funnel—particularly for prospecting, lookalike modelling, and extending campaign reach via programmatic buying.

Customer data platforms (CDPs): Marketers’ new favourite tool

As privacy regulations tightened and cookies began to fade, customer data platforms (CDPs) rose in popularity.

While they may sound similar to DMPs, CDPs serve a different role: they focus on first-party data, providing a single customer view across owned touchpoints.

CDPs integrate data from websites, apps, CRM systems, and email platforms to build persistent, privacy-compliant profiles. These profiles help personalise marketing campaigns, trigger lifecycle messages, and improve customer retention.

📌 Unlike DMPs, which are ad-focused and often anonymous, CDPs are identity-centric and built for long-term engagement.

Popular CDPs include Segment, Treasure Data, and Salesforce CDP.

Data clean rooms: Collaboration without exposure

One of the biggest challenges in AdTech today is how to collaborate across companies without compromising user privacy. Enter data clean rooms—secure environments where 2 or more parties can compare datasets, utilise each other’s data for targeting and measurement, and generate insights, but without sharing raw data.

For example, a retailer and a consumer goods brand might upload their first-party data into a clean room. The data is typically uploaded to separate databases so that the two data sets are never combined together.

Inside the clean room, the two datasets are matched in a privacy-safe way using a common identifier, e.g. a hashed email address, allowing joint activation and measurement without exposing individual user records.

Clean rooms are critical in the post-cookie era, where interoperability must be balanced with compliance. Leaders in this space include Google Ads Data Hub, Amazon Marketing Cloud, Infosum, Decentriq, Aqilliz, and Snowflake’s collaboration tools.

Data brokers

Data brokers are companies that collect, package, and sell data about individuals.

At their core, data brokers compile information about people—not from a single source, but from many.

They collect this data from:

- Public records – property ownership, court filings, licenses.

- Commercial sources – credit card transactions, loyalty programs.

- Digital behaviour – web browsing, app usage, purchase histories.

- Offline data – store receipts, event attendance, subscriptions.

They then organise this information into profiles and segments—from high-level demographics to highly specific interests like “new homeowner,” “SUV buyer,” or “organic food enthusiast.”

These segments are then sold to marketers, DMPs, or directly to DSPs for audience targeting.

While many data brokers originally just collected data and sold it to data platforms for activation, many are now data platforms themselves. However, the data platform offering varies among data brokers.

For example, LiveRamp is a data broker but has an established and vast data platform offering. Other data brokers may simply provide software to allow companies to view or access the data, without having many integration or activation capabilities.

While data brokers have powered much of the precision in programmatic advertising, they’ve also become a flashpoint in the privacy debate. Their role is increasingly scrutinised by regulators and privacy advocates.

As the industry shifts toward first-party data and ethical data sourcing, data brokers are under pressure to evolve—or risk becoming obsolete.

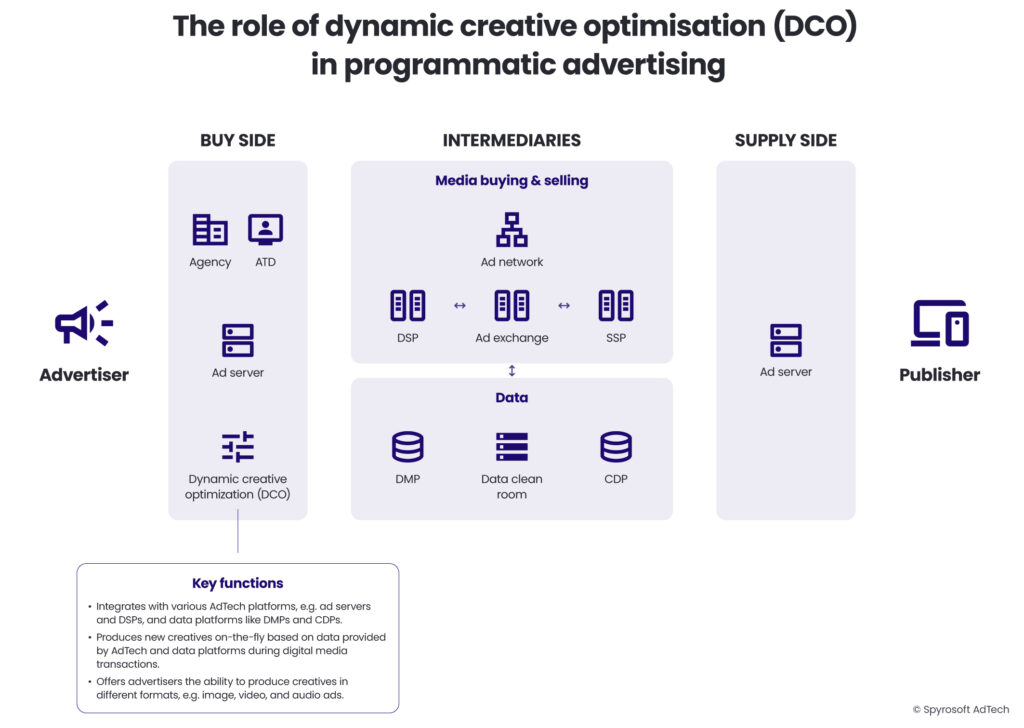

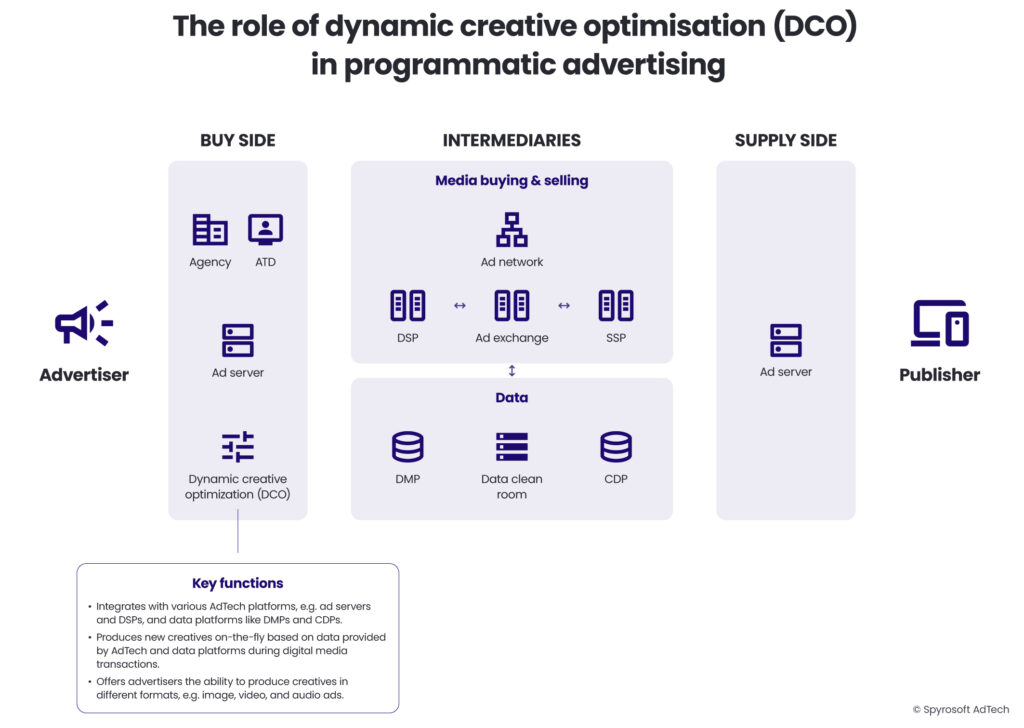

Dynamic creative optimisation (DCO)

With all this data flying around, the next question became: How do you make sure your ad creative is as relevant as your targeting?

Dynamic creative optimisation (DCO) answers that question.

DCO platforms generate personalised ads on the fly based on real-time signals—location, device, behaviour, time of day, weather, and more.

For instance, a sportswear brand might show one user a “Running shoes for rainy days” banner and another user a “Summer trail gear” ad, using the same ad slot but different creative elements.

DCO requires tight integration between creative assets, data feeds, and delivery platforms. It transforms ads from static messages into living, breathing content tailored to each viewer.

A summary of the DCO process:

- The advertiser or agency prepares a campaign and designs modular creative assets.

- The DSP bids on impressions in real-time via the ad exchange.

- The ad exchange sends bid requests to multiple SSPs (supply-side platforms), which represent various publishers.

- If the DSP wins the bid, then the DCO tool assembles a creative based on the user and contextual data provided in the bid request. The ad is then delivered to the publisher and displayed to the user.

DCO vs. traditional A/B testing

It’s worth noting that DCO is not the same as A/B testing.

While A/B testing compares a few static creative versions over time, DCO automates the creation, delivery, and optimisation of dozens—or even hundreds—of creative variations simultaneously. It’s faster, more scalable, and deeply integrated with the programmatic buying process.

The interconnected web of AdTech

Each of the platforms discussed in this chapter serves a distinct function. But they don’t operate in isolation—they are deeply interconnected.

An advertiser might use a CDP to create audiences, activate it through a DSP, serve ads tracked by an ad server, and optimise performance with a DCO platform.

What once took entire departments of media planners and direct sales reps is now executed in milliseconds through a global network of platforms, APIs, and bidding engines.

The 3 key programmatic advertising processes

Now that we understand the platforms that power digital advertising, we turn to the core processes that drive their interaction: how ads are targeted, how exposure is controlled, and how results are measured.

These three processes—ad targeting, frequency capping, and measurement & attribution—are the operational backbone of programmatic advertising.

Each plays a critical role in ensuring that ads reach the right person, at the right time, the right number of times, and with measurable outcomes.

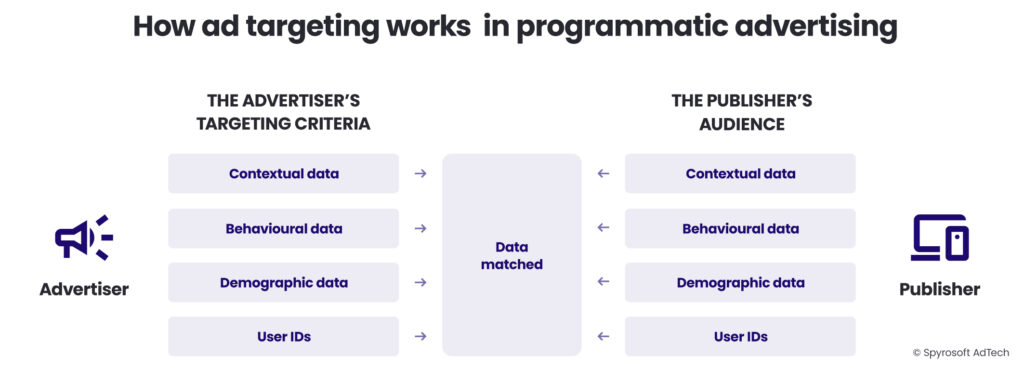

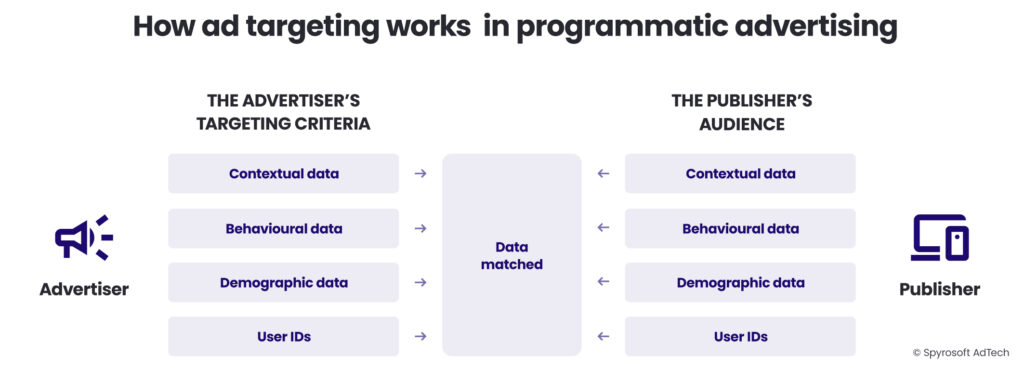

1. Ad targeting: Reaching the right person at the right time

At the heart of programmatic advertising is the ability to serve personalised ads to specific users in real time.

This is what sets digital advertising apart from traditional media—it’s not about broadcasting to broad segments, but about narrowcasting to individuals based on who they are, what they’ve done, and what they’re likely to do next.

In the early days, targeting was limited to simple demographics and contextual cues—placing ads for running shoes on sports news sites, for example. But as data became more available and machine learning more advanced, targeting evolved into something far more granular.

Modern ad targeting uses dozens of signals, such as:

- First-party data collected by brands from their websites and apps.

- Third-party audience segments from data brokers or DMPs.

- Behavioural data, such as browsing history, video views, or purchase intent.

- Contextual data, based on the content of the page or app.

- Device, time of day, and location signals.

The goal is simple: maximise relevance.

If a user has been searching for travel deals, they’re more likely to engage with an airline ad than a general audience. If someone is reading a recipe on their phone at 6 PM, a food delivery offer might convert better than a travel ad.

But effective targeting also raises questions of privacy, transparency, and fairness.

As regulatory frameworks like GDPR and CCPA gain teeth, advertisers must walk a fine line—delivering relevant experiences while respecting user consent and data protection.

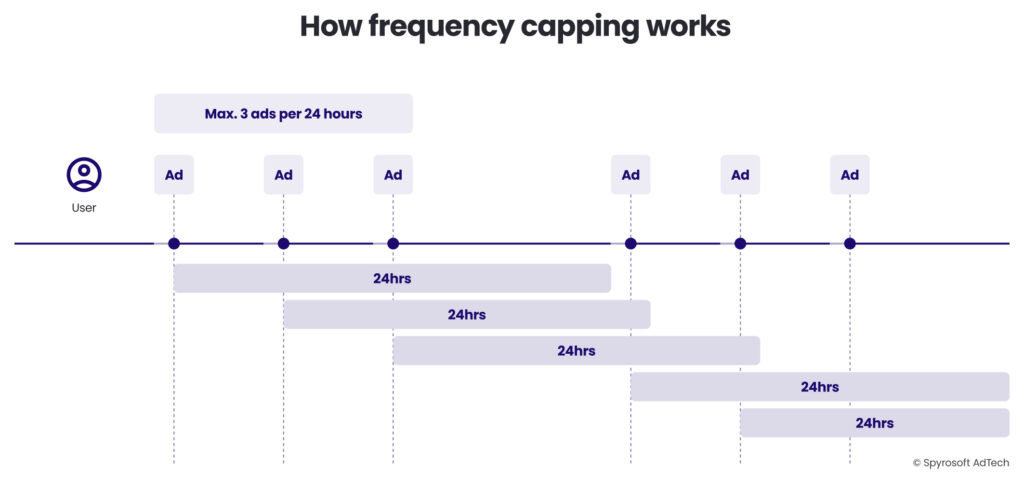

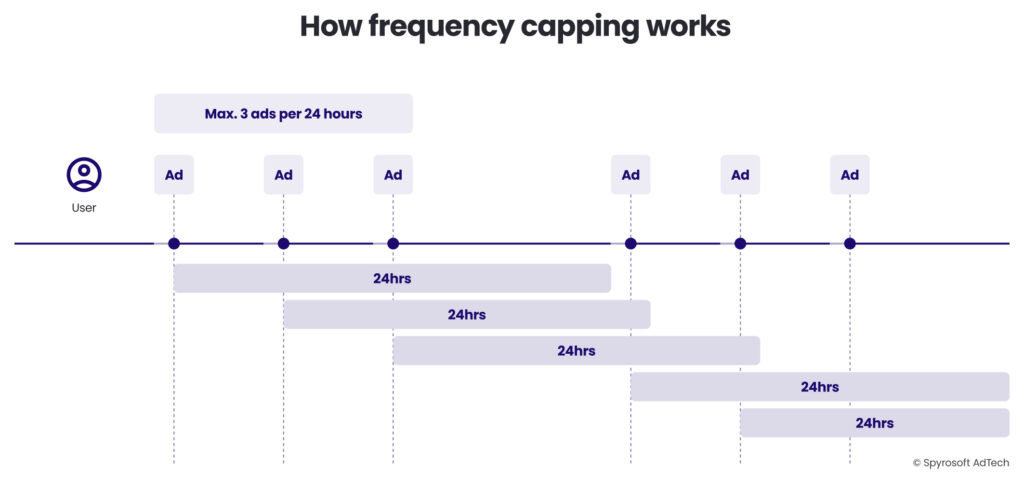

2. Frequency capping: Preventing “ad fatigue”

If ad targeting is about who you show an ad to, frequency capping is about how often you show it.

Repetition can be powerful in advertising, but it’s a delicate balance. Too little exposure, and your message is missed. Too much, and you risk annoying the user—or worse, wasting your ad budget on someone who’s already made up their mind.

Frequency capping sets limits on how many times a specific ad (or campaign) is shown to a single user over a given period—say, no more than three times per day or ten times per week.

This process is especially critical in programmatic advertising, where the same user may visit dozens of sites in a day, and multiple DSPs may try to serve them the same ad.

Before centralised platforms and ID graphs, this was nearly impossible to manage across domains. A user might be shown the same ad 20 times from different vendors without realising it. Today, with shared identity systems and better cross-channel tracking, frequency capping has become more accurate—even across devices and environments.

Done right, frequency capping improves both user experience and campaign efficiency. It ensures that your budget isn’t being drained on overexposed audiences, and that users don’t walk away with negative brand impressions.

3. Measurement & attribution: Understanding what works

Programmatic advertising is only as valuable as its ability to measure outcomes. Whether you’re running a brand awareness campaign or a performance-driven initiative, you need to know: Did the ad work?

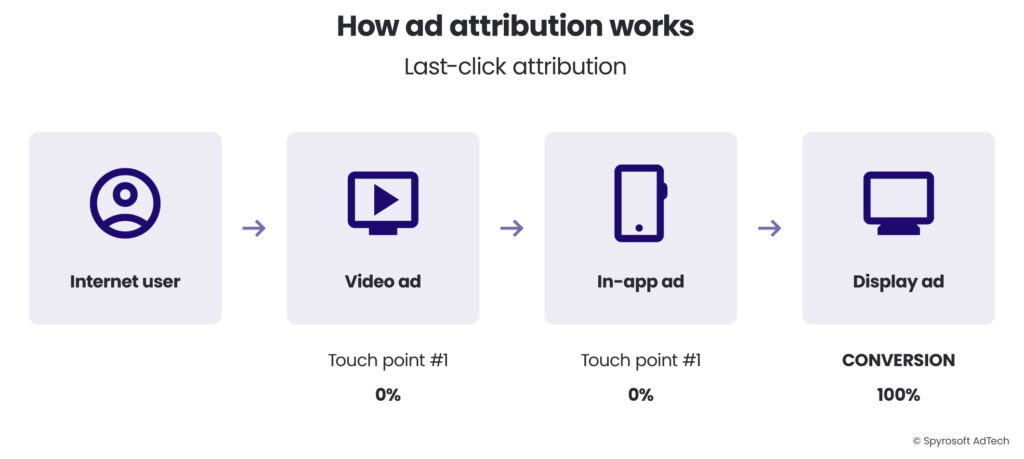

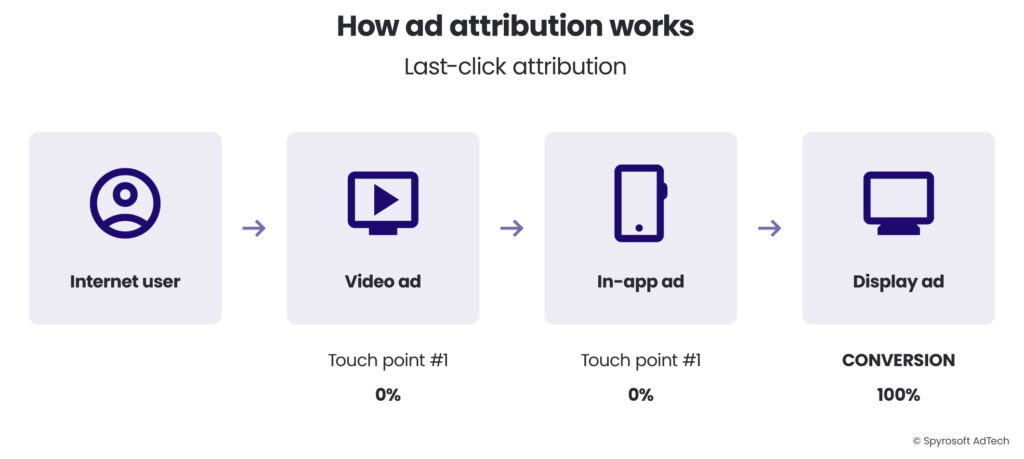

Measurement covers a range of metrics—impressions, clicks, conversions, viewability, engagement, and return on ad spend (ROAS). But raw numbers are only part of the picture. The real challenge lies in attribution—determining which ad touchpoint actually drove the desired action.

Attribution answers questions like:

- Did the display ad drive the user to purchase, or was it the email campaign?

- How much credit should be given to the video ad viewed a week before conversion?

- What role did a mobile click vs. a desktop visit play in the final outcome?

There are several models used to assign value to different touchpoints:

- Last-click attribution: 100% credit goes to the last interaction before conversion

- First-click attribution: 100% credit goes to the first touchpoint

- Linear attribution: Credit is split equally across all touchpoints

- Time decay: More credit is given to recent interactions

- Algorithmic attribution: Machine learning assigns credit based on observed patterns

An example of how last-click attribution across three touchpoints.

With the demise of third-party cookies and stricter privacy laws, measurement is shifting toward incremental (aka incrementality) testing, media mix modelling, and clean room analytics—methods that don’t rely on direct user-level tracking, but still offer insight into campaign performance.

Measurement is also increasingly real-time. Marketers can optimise campaigns mid-flight, adjusting bids, creatives, or targeting based on what’s working and what’s not.

This level of agility was unthinkable in the pre-digital era.

Why these processes matter

Ad targeting, frequency capping, and attribution may sound like technical details—but together, they define the user experience and the campaign’s success.

Targeting ensures relevance. Frequency capping ensures control. Measurement ensures accountability.

They also reflect the central promise—and the ongoing tension—of programmatic advertising: delivering precision at scale, without compromising the human experience.

Mastering these processes is essential for anyone looking to navigate the AdTech ecosystem with confidence.

How companies make money in programmatic advertising

The programmatic advertising ecosystem creates multiple revenue streams for different participants in the supply chain.

Unlike traditional advertising models where revenue paths were relatively straightforward, programmatic’s complex ecosystem has created diverse monetisation opportunities.

Let’s explore how the two primary stakeholders – advertisers and publishers – generate returns within this system.

How advertisers make money

While advertisers are typically seen as spending money rather than earning it through advertising, they actually generate returns in several important ways:

By advertising their products and services

The most fundamental way advertisers generate revenue is through the direct business impact of their advertising campaigns:

Brand awareness campaigns: Though less directly measurable, brand advertising builds long-term value through increased recognition and consideration.

Direct response advertising: Campaigns designed to trigger immediate consumer action generate measurable revenue.

For example, an ecommerce retailer running dynamic product ads might achieve a 400% return on ad spend (ROAS), earning $4 for every $1 invested in programmatic advertising.

Customer lifecycle optimisation: Programmatic platforms enable advertisers to target users at different stages of the customer journey, from acquisition through to retention.

A subscription service might determine that retention-focused programmatic campaigns deliver 3x higher lifetime value compared to continuously acquiring new customers.

By selling their data

Beyond direct advertising returns, sophisticated advertisers have found ways to monetise the data they collect through their campaigns:

Second-party data partnerships: Advertisers with valuable first-party data can form revenue-sharing partnerships with complementary brands.

For instance, an airline might license its traveler data to hotel chains, creating a new revenue stream while helping partners improve their targeting.

Data cooperative participation: Some advertisers participate in industry data cooperatives, pooling anonymised customer insights in exchange for broader data access and potential revenue sharing.

These arrangements allow companies to monetise their customer data while gaining valuable insights from other participants.

Media network development: Major retailers like Walmart, Target, and Amazon have transformed from pure advertisers into media networks, selling access to their customer data and digital real estate to other brands.

Similarly, video-streaming services like Netflix and Disney+ have built advertising businesses to monetise their audience and create a new revenue stream. This “everything is an ad network” trend has created billion-dollar revenue streams for companies that were previously only on the spending side of advertising.

How publishers make money

Publishers have traditionally relied on advertising as their primary revenue source, but as programmatic advertising evolved, so too has publishers’ monetisation options.

Below are the main ways publishers make money.

Ad revenue

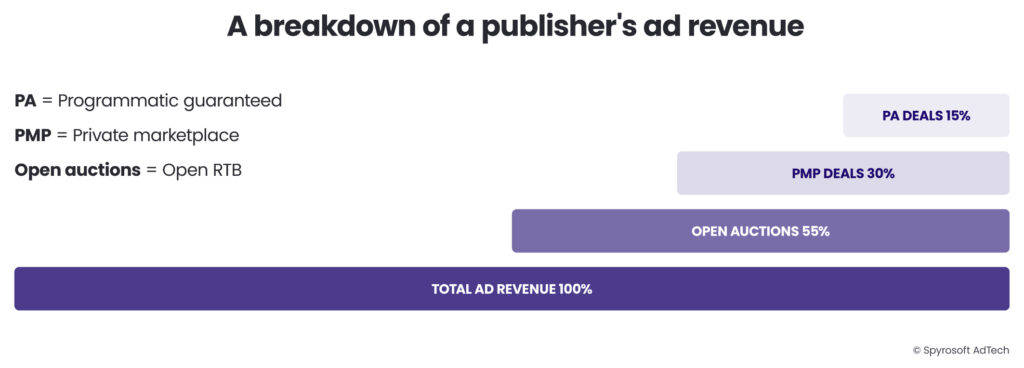

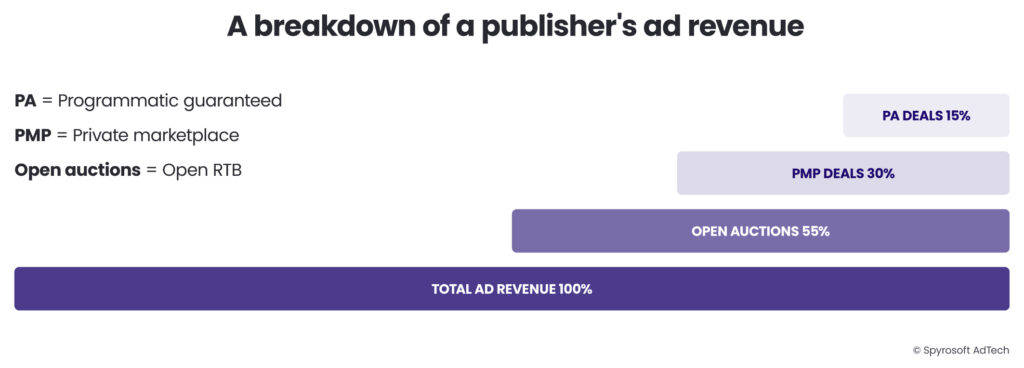

The most direct revenue source for publishers comes from selling their inventory programmatically:

Open auction revenue: Publishers make their inventory available through supply-side platforms (SSPs) and ad exchanges to be purchased in real-time bidding (RTB) auctions. While open auctions typically yield lower CPMs (cost per thousand impressions), they improve fill rates and deliver baseline revenue.

Private marketplace deals (PMPs): Publishers negotiate preferred deals with specific advertisers at premium rates.

Programmatic guaranteed: Direct deals executed through programmatic channels provide publishers with guaranteed revenue commitments at fixed CPMs. This combines the efficiency of programmatic with the predictability of traditional direct sales.

Header bidding adoption: Publishers implementing advanced auction technologies like header bidding have reported revenue increases of 20-50% by allowing multiple SSPs to compete simultaneously for each impression, driving up bid prices.

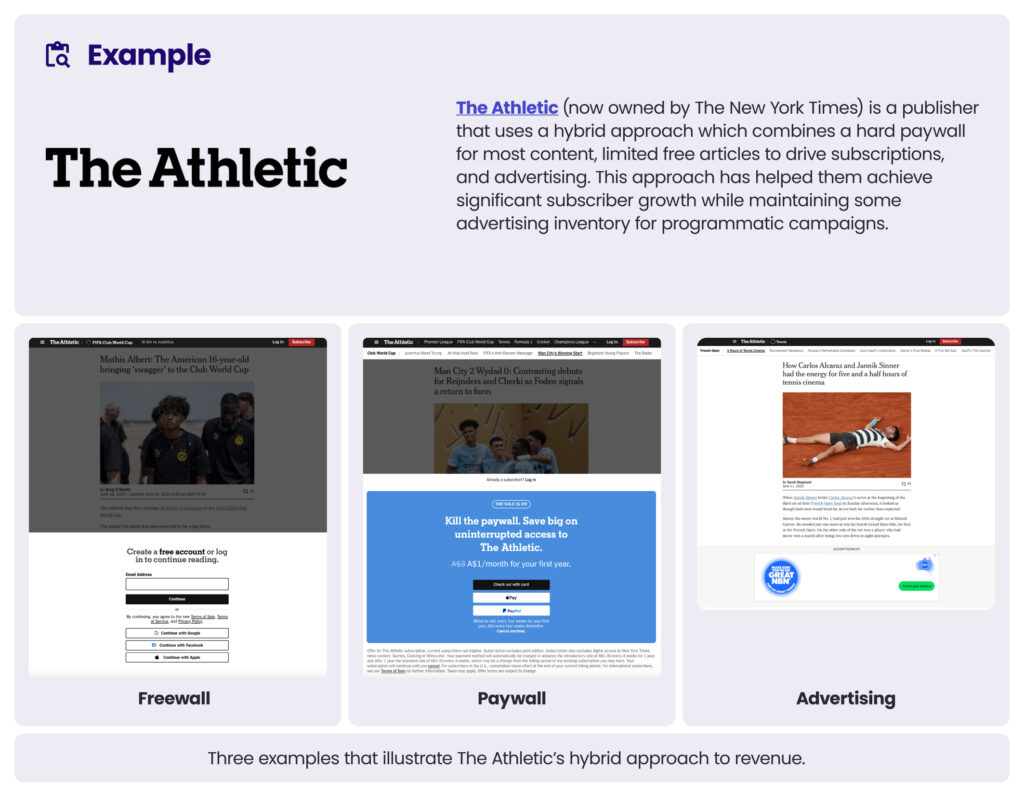

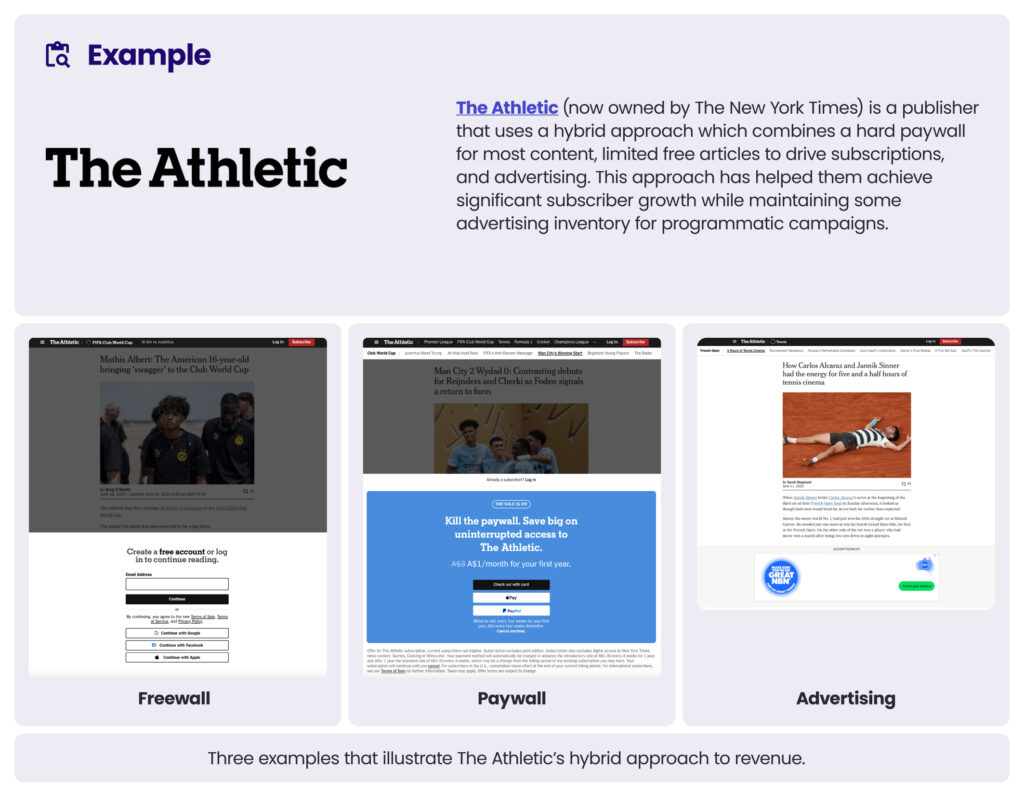

Paywalls and subscription models

As programmatic ad yields have fluctuated, many publishers have developed subscription revenue streams:

Hard paywalls: Complete content restriction requiring subscription for access. The New York Times has successfully implemented this model, growing to over 11 million digital subscribers and reducing their reliance on advertising revenue.

Metered paywalls: Allowing limited free access before requiring payment. This hybrid approach maintains some ad inventory while developing subscription revenue.

Dynamic paywalls: Using programmatic technology to determine which users are most likely to subscribe, showing paywall prompts to high-potential visitors while maintaining ad-supported experiences for others.

Ad-free subscription tiers: Offering premium, ad-free experiences for paying subscribers while serving programmatic ads to non-subscribers.

By selling their data

Publishers with valuable audience data have developed data monetisation strategies:

Audience segments: Publishers package their first-party data into targetable segments that advertisers can purchase through DMPs (data management platforms) or directly through their SSPs.

Publisher data marketplaces: Some larger publishers have created their own data marketplaces, allowing advertisers to purchase audience segments derived from their content consumption patterns and declared user information.

Data licensing agreements: Publishers with specialised audiences may license their data to third parties for research, market intelligence, or inclusion in broader data products.

Publisher consortiums: Groups like the Ozone Project in the UK combine publisher data across multiple premium sites to create scale that can compete with the walled gardens, creating new revenue opportunities through collective data assets.

The diversification of revenue sources in programmatic advertising reflects the ecosystem’s maturation.

Both advertisers and publishers continue to develop increasingly sophisticated approaches to monetisation, finding value not just in the buying and selling of impressions, but in the data generated throughout the process.

As companies become less reliant on third-party cookies and privacy regulations tighten, these data monetisation strategies are evolving toward more privacy-compliant models based on first-party relationships and aggregated insights.

How AdTech companies make money

Developing and operating advertising technology platforms is an expensive undertaking, requiring significant investment in infrastructure and personnel—including developers, engineers, managers, and sales teams.

To remain viable, AdTech vendors must deliver high-performing products while ensuring their business models generate enough revenue to cover costs and turn a profit.

Since the early days of online advertising, technology providers have typically earned revenue by applying commissions and service fees—often calculated as a percentage markup on media spend.

Historically, many AdTech platforms added margins of around 30% to the cost of media. However, increased competition and growing demand for transparency around media pricing and platform fees (often called the “AdTech tax”) have driven these markups down.

Today, many AdTech companies claim their fees—or “take rates”—have dropped to single-digit percentages.

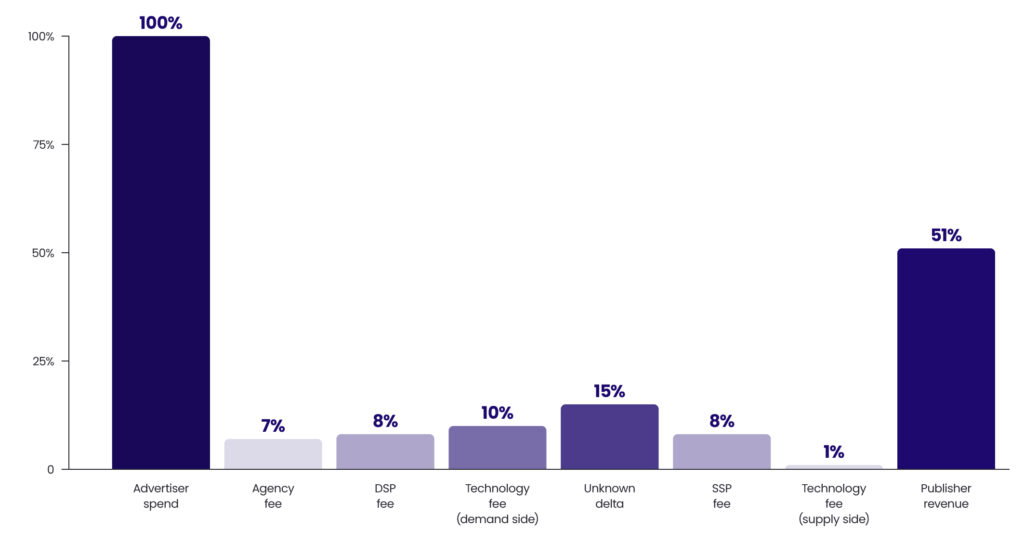

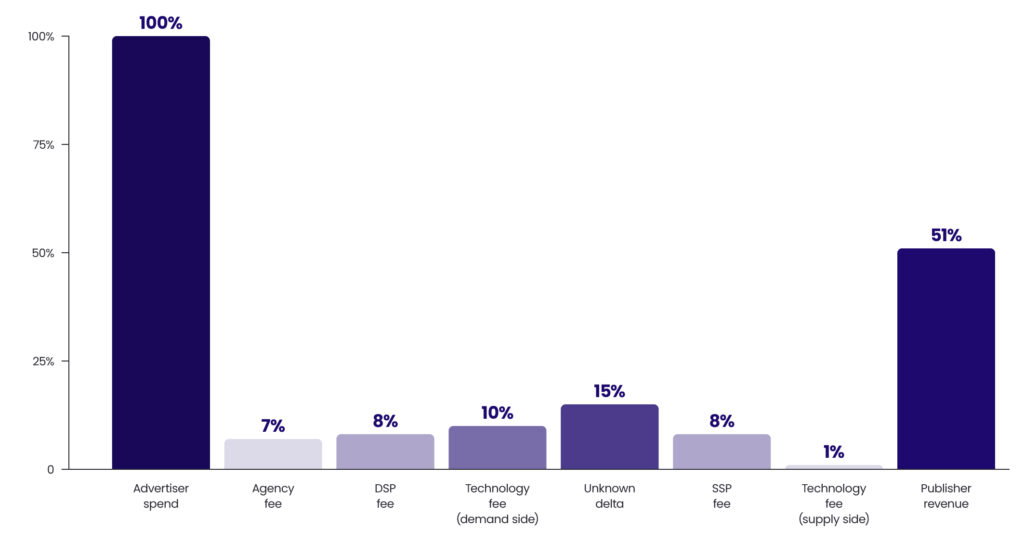

Determining an AdTech platform’s fee can be difficult, but a 2020 report from the UK’s advertiser trade body, ISBA, conducted a study alongside the Association of Online Publishers (AOP) and PwC into transparency in the digital media supply chain to identify what share of an advertisers ad budget was going to intermediaries.

The report found that the take rates from intermediaries ranged from 1% to 10%. However, the report discovered that 15% of an advertiser’s ad budget couldn’t be attributed to an intermediary, referred to as the “unknown delta”. This highlights the complex and fragmented nature of the digital media supply chain.

Next chapter

Chapter 03: How Digital Media Is Bought, Sold and Measured

Download the PDF & join our waiting list

Fill in the form to download the PDF version and get notified when the next chapters are released.