Chapter 01: The History of AdTech and Programmatic Advertising

The programmatic advertising industry dates back to the mid-1990s, when the internet became widely available. Its history is marked by booms and busts, rapid technological innovation, and disruptive forces.

In this chapter, we’ll take a look at the history of programmatic advertising — starting with the very first online ad in 1994, followed by the introduction of the first AdTech companies, and concluding with the rise of artificial intelligence.

Key takeaways

- The first online advertisement appeared in 1994, marking the beginning of digital advertising. Manually inserted banner ads dominated early online advertising, replicating print media strategies online.

- Ad servers emerged in the late 1990s to allow advertisers and publishers to manage digital ads more efficiently.

- Ad networks emerged in the 2000s, helping advertisers scale campaigns across multiple websites.

- The programmatic revolution in the 2010s introduced automation and real-time bidding (RTB).

- Today, privacy regulations and AI are reshaping the industry, with a shift toward first-party data strategies.

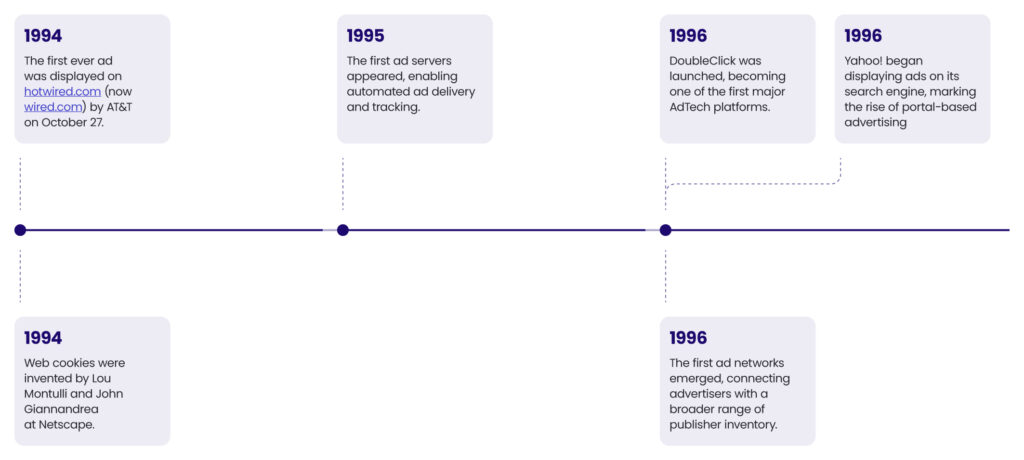

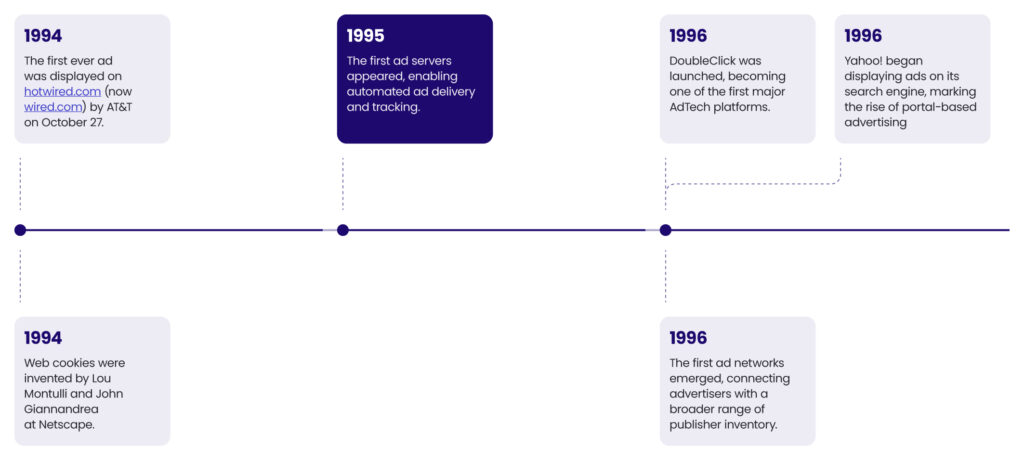

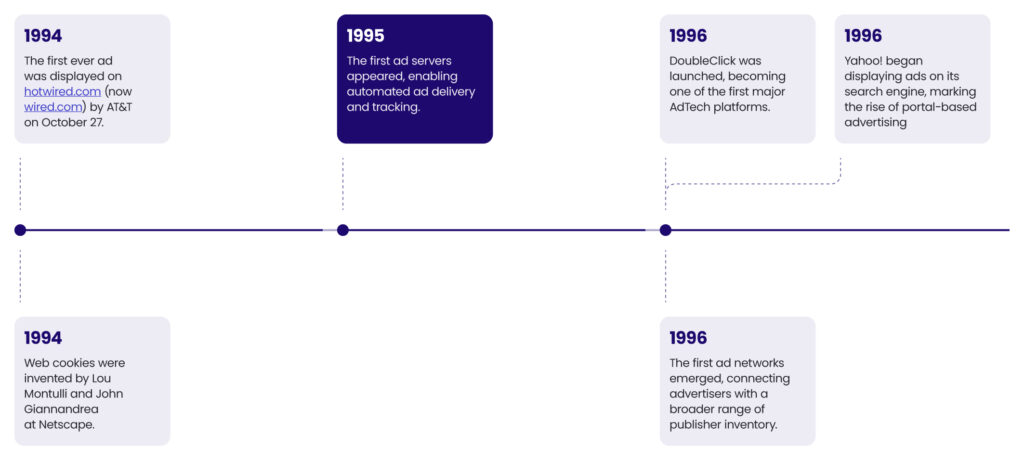

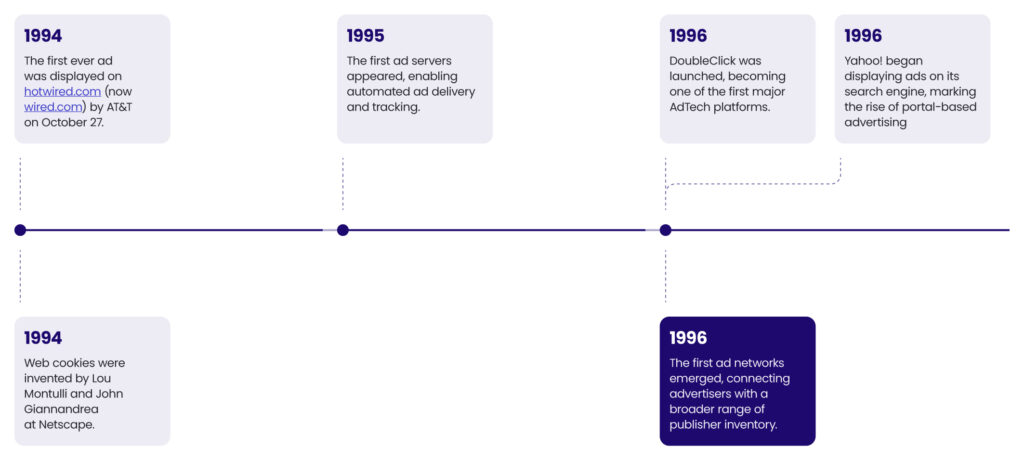

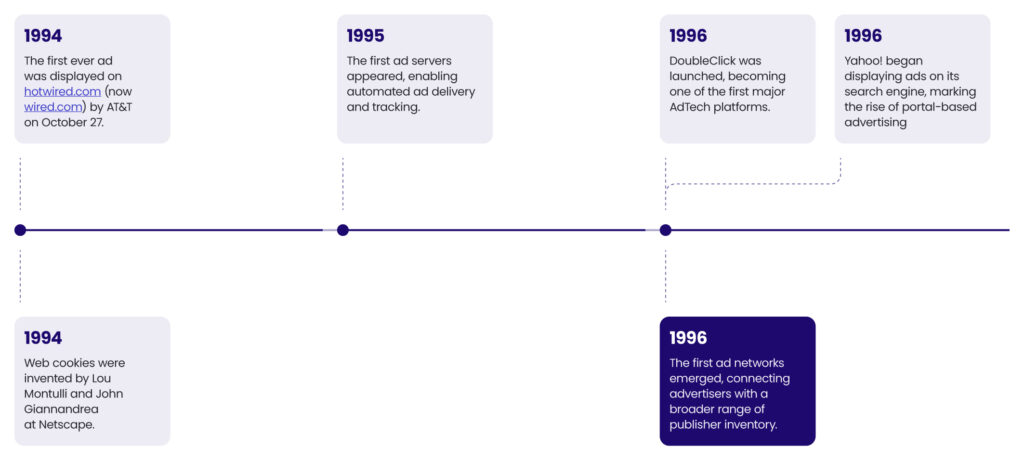

1994 to 1999: The beginning of programmatic advertising

Before the internet, advertising was a one-way street—brands broadcast their messages through TV, radio, print, and outdoor billboards. Consumers had little control over the ads they saw, and advertisers relied on broad audience segmentation based only on demographics and media consumption habits.

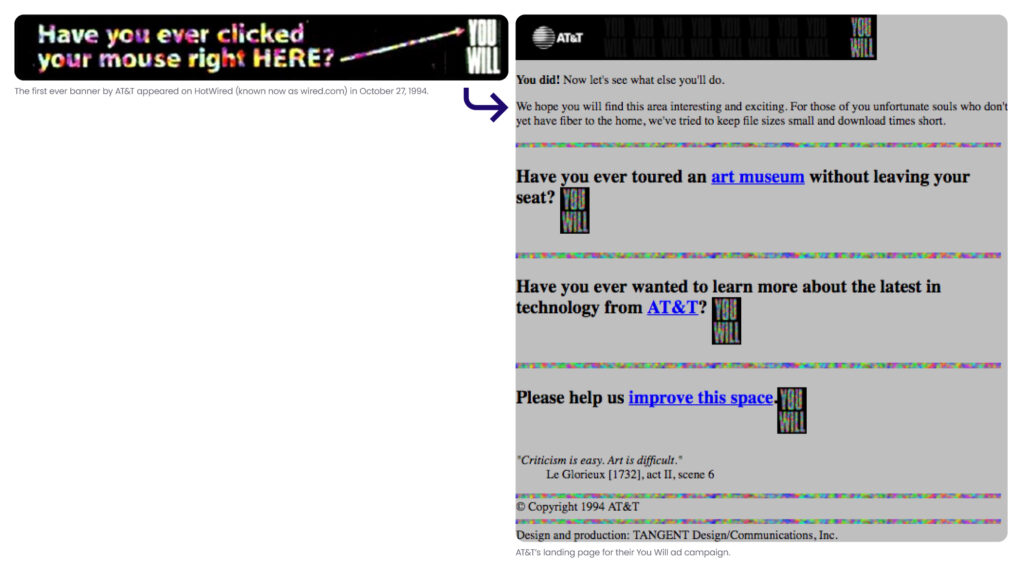

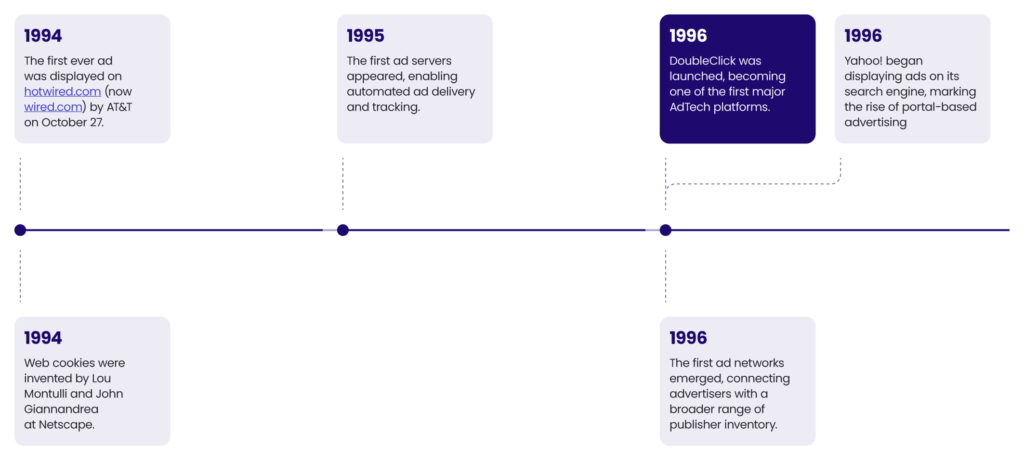

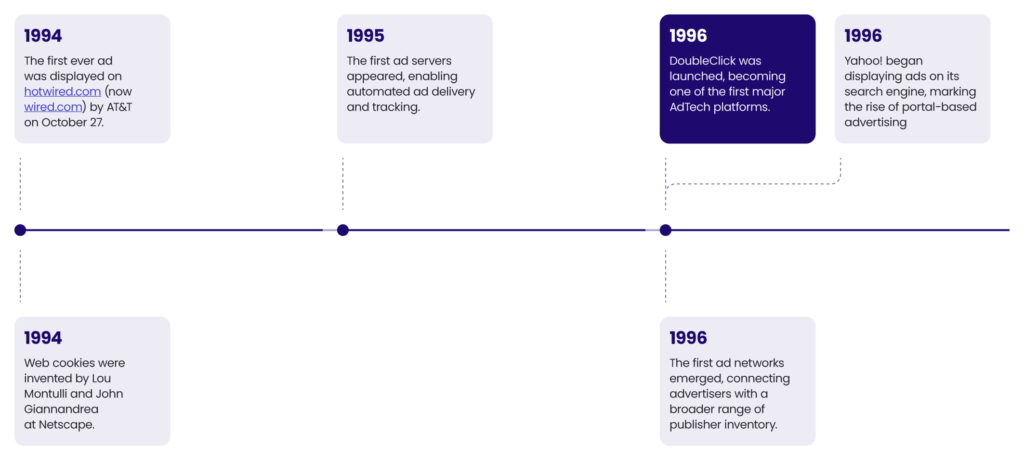

That changed on October 27, 1994, when AT&T displayed the first-ever digital advertisement on HotWired, the online version of Wired magazine. This banner ad, measuring 468×60 pixels, was simple yet revolutionary. It featured a cryptic message:

When clicked, it redirected users to an AT&T promotional campaign landing page.

This experiment in online advertising was a massive success, achieving an eye-watering click-through rate (CTR) of 44%. The figure would be unheard of today, where the typical CTR for display ads hovers around 0.1–0.3%.

📌 Why was the AT&T ad revolutionary?

- It was the first interactive ad. Unlike in traditional print or TV ads, users could click on the banner, actively engaging with the brand.

- For the first time, advertisers could track user actions like clicks and visits.

- Digital ads could reach a global audience instantly, unlike regional or national print campaigns.

The 1994 AT&T banner ad may seem simple by today’s standards, but it set the stage for an entire industry. Would a banner ad like this capture users’ attention today as it did in 1994 for AT&T? Definitely not. But it was the spark that ignited the AdTech revolution.

The first ad server

AT&T’s banner was a big step in its own right, but the process itself was still far from perfect.

In the early days of digital advertising, there was no way to measure success beyond basic metrics, such as impressions and clicks.

Every ad buy had to be manually negotiated with individual website owners, and once an ad was placed, there was no way to optimise or track its performance.

Without data, automation, or targeting, digital advertising was just a digital version of print advertising—ads were placed manually, and their effectiveness was mostly guesswork.

This lack of efficiency led to a critical question: How can advertisers track, manage, and optimise their digital ad campaigns in real time?

The answer? Ad servers.

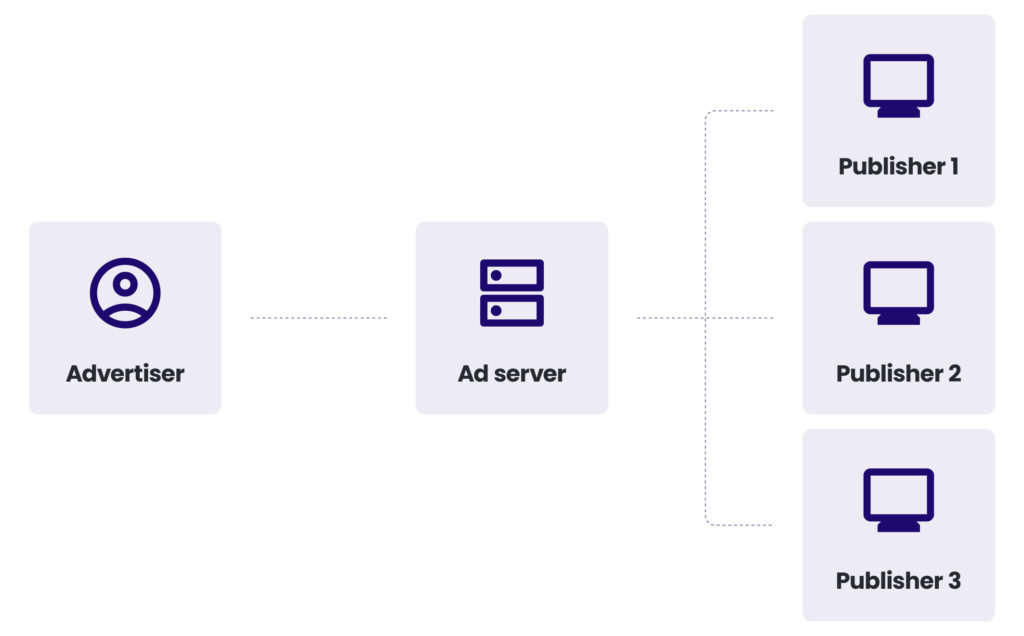

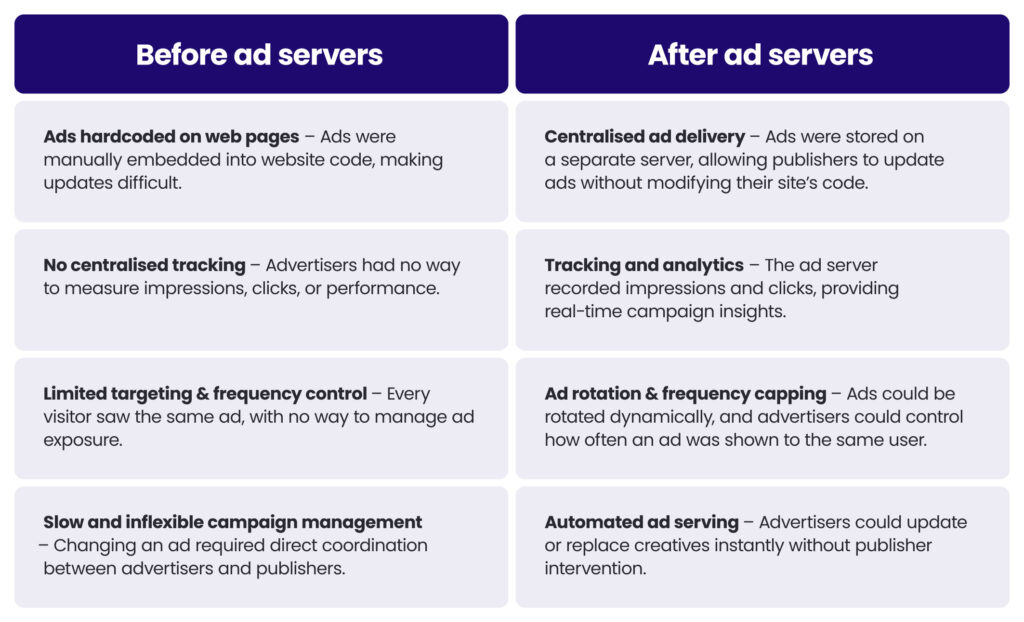

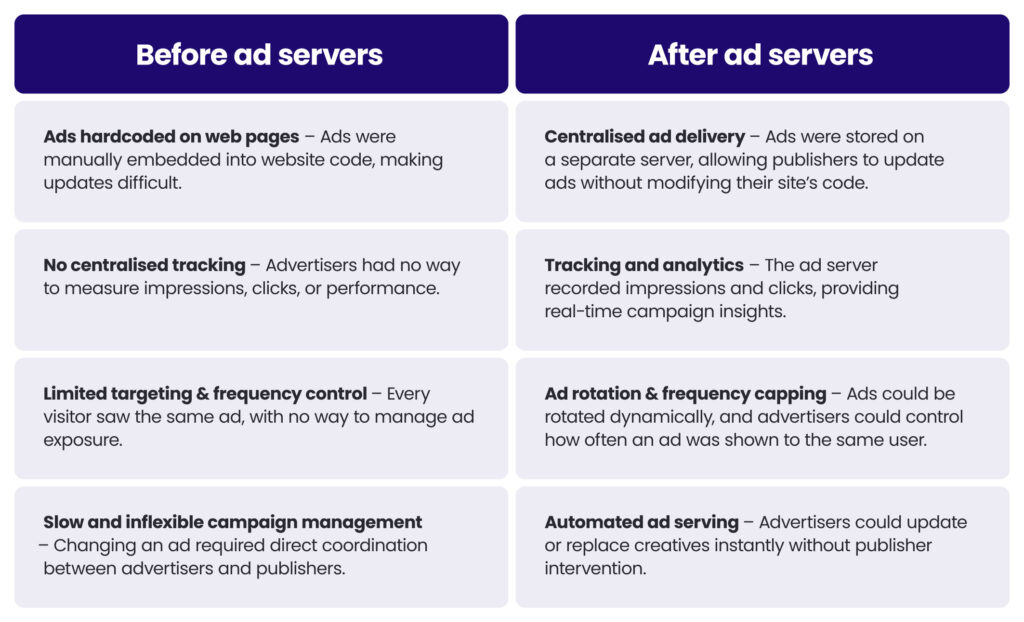

An ad server is a platform that stores, delivers, and tracks digital advertisements across websites, mobile apps, and other digital environments.

It enables advertisers and publishers to manage ad campaigns, target audiences, rotate creatives, and measure performance metrics such as impressions and clicks.

This might seem basic by today’s standards, but at the time, it was a radical innovation. Ad servers allowed advertisers to shift from guesswork to data-driven decision-making, laying the foundation for modern performance-based advertising.

The first ad servers had limited targeting capabilities, relying mainly on information contained in the user agent string, which is a line of text that a web browser automatically sends to a web server when requesting a page.

The types of information contained in a user agent string include the browser type and version, the language or locale, and the computer’s operating system.

Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 5.0; Windows 98; DigExt)An example of a user agent string. Ad servers would use this information to decide which ads to show to a given user.

Companies would set up campaigns using insertion orders (IOs), which are legal agreements between an advertiser and publisher. The insertion orders outline the details of the campaign, such as:

- The campaign’s name

- Start and end dates

- Budget and maximum spend

- The pricing model, e.g. CPM, CPC, CPA

- Ad format, e.g. display or video ad

- Ad placement, e.g. rectangle ad or full-page takeover

Why was the ad server a breakthrough?

- Automated ad delivery: Before ad servers, placing an ad online on a website was a slow, manual process. The ad server automated ad placements, allowing advertisers to scale campaigns more efficiently.

- Performance tracking: For the first time, advertisers could see how many times their ads were displayed (impressions) and how many users clicked on them (CTR). This data-driven approach transformed digital advertising from a static model to a measurable, results-oriented system.

- Multi-site campaign management: Instead of managing separate ad deals with individual websites, advertisers could now run campaigns across multiple publishers from one platform. This centralised approach made online advertising much more scalable.

- Dynamic ad rotation: The ability to rotate ads in real time meant that different users could see different ads. This marked the beginning of ad targeting, as advertisers started experimenting with different creatives to optimise engagement.

The first ad server

When the internet first started to gain popularity in the mid-1990s, a few companies saw a new opportunity: online advertising.

One of the first companies to capitalize on this exciting opportunity was FocaLink Media Services, who are often touted as one of the first companies to build an ad server.

FocaLink Media Services was founded in 1995 by Dave Zinman and Jason Strober and launched its ad server, called Smart Banner, in the same year. The company’s first customers included Intel and Saturn.

In 1998, FocaLink Media Services merged with ClickOver, rebranded as AdKnowledge and expanded its capabilities to include more advanced targeting and optimisation features. A year later, AdKnowledge was acquired by CMGi, one of the leading internet investment firms of the dot-com era.

By the late 1990s, competition in the AdTech space was intensifying. Companies like NetGravity and DoubleClick had developed their own, more sophisticated ad-serving technologies.

Later, as the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, many early AdTech companies struggled to survive, and AdKnowledge eventually faded into obscurity.

Even though FocaLink itself didn’t evolve to become a current-day market leader, its invention of the ad server shaped the future of digital advertising:

- Ad servers led to the rise of ad networks – With ad servers making it easier to manage ads across multiple sites, companies began building ad networks to aggregate ad inventory.

- It paved the way for DoubleClick’s DART system – DoubleClick’s DART ad server, launched in 1996, improved upon the ad server model and became the dominant force in the industry.

- Enabled programmatic advertising – Without the automation and tracking that ad servers introduced, programmatic advertising would not have been possible.

Before the introduction of ad servers, if an advertiser wanted to run a campaign on multiple websites, they would need to manually contact each website owner, negotiate a placement, and provide the ad creative. If an advertiser wanted to swap out an ad or adjust a campaign, they would have to go through this process from scratch.

DoubleClick and the evolution of the AdTech ecosystem

With the introduction of ad servers, advertisers and publishers, for the first time, had a way to automate the serving of digital ads, track impressions, and measure performance without direct, manual intervention.

However, with the internet’s explosive growth in the late 1990s, it became clear that ad serving alone wasn’t enough to keep pace with the growing complexities of online advertising.

More businesses were launching websites, banner ads were multiplying, and advertisers wanted better ways to target users and optimise ad spend. This demand led to the rise of new AdTech platforms.

In 1996, DoubleClick, founded by Kevin O’Connor and Dwight Merriman, introduced one of the first major third-party ad servers, adding capabilities like frequency capping, ad rotation, and campaign tracking.

This was an important step toward making online advertising more data-driven and measurable.

Yet, even with DoubleClick’s improvements, a fundamental challenge remained: advertisers had to negotiate directly with each publisher to buy ad space.

This process was time-consuming, inefficient, and unsustainable in a digital landscape that was rapidly growing.

The industry needed a more scalable solution—one that could match advertisers with available ad inventory at scale, across multiple websites.This problem led to the rise of ad networks, the first true evolution of the AdTech ecosystem.

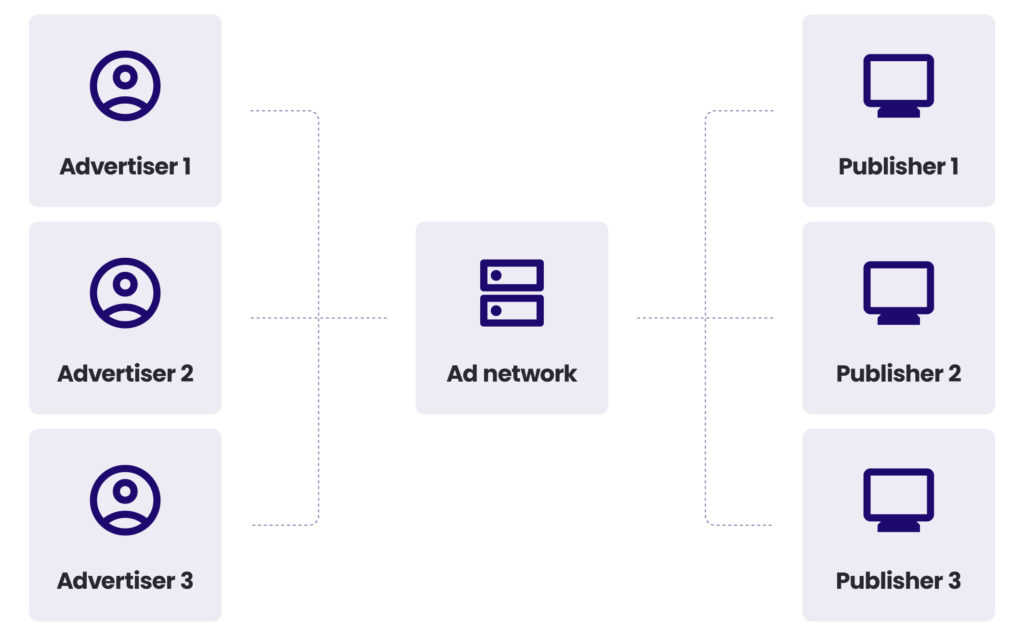

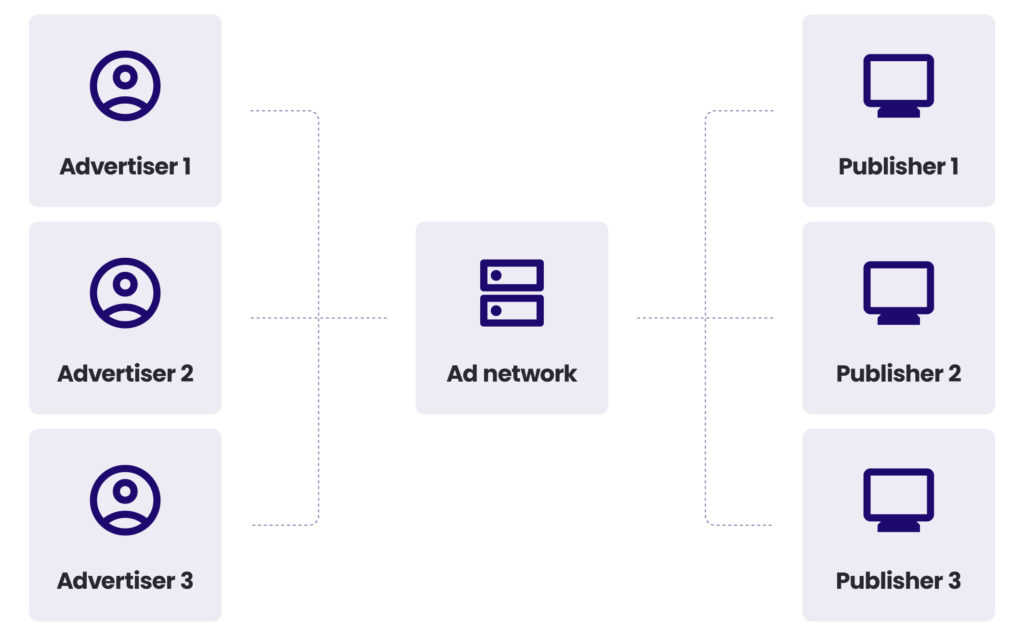

Ad networks

In the late 1990s, ad networks emerged to connect advertisers with multiple publishers at once, streamlining the process of buying and selling ad space.

Instead of negotiating individual deals, advertisers could now buy inventory in bulk from an ad network, which acted as an intermediary.

Early pioneers, such as Flycast (founded in 1996) and 24/7 Media (founded in 1997), built inventory pools from various publishers, allowing advertisers to distribute their ads across multiple websites through a single platform.

This approach solved several key issues:

- Increased efficiency – Advertisers no longer had to contact each publisher separately.

- Better monetisation for publishers – Websites could sell their ad space more easily, especially unsold (remnant) inventory.

- Basic targeting – Ads could be grouped by content category, audience segment, or geographic location.

However, as effective as ad networks were, they introduced a new set of challenges.

Advertisers had limited visibility into where their ads appeared, and publishers struggled to maximize their revenue, as pricing was often fixed or bundled without real-time competition.

This lack of transparency and efficiency paved the way for new technologies and media-buying processes.

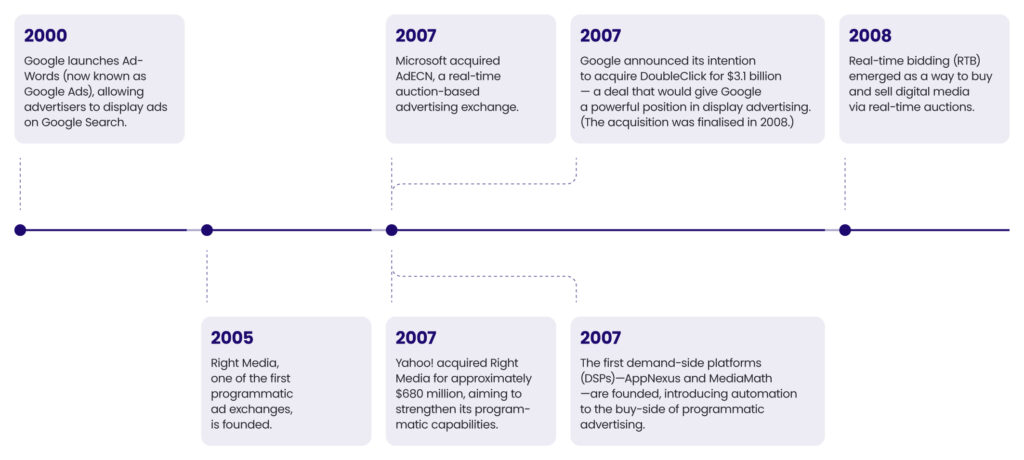

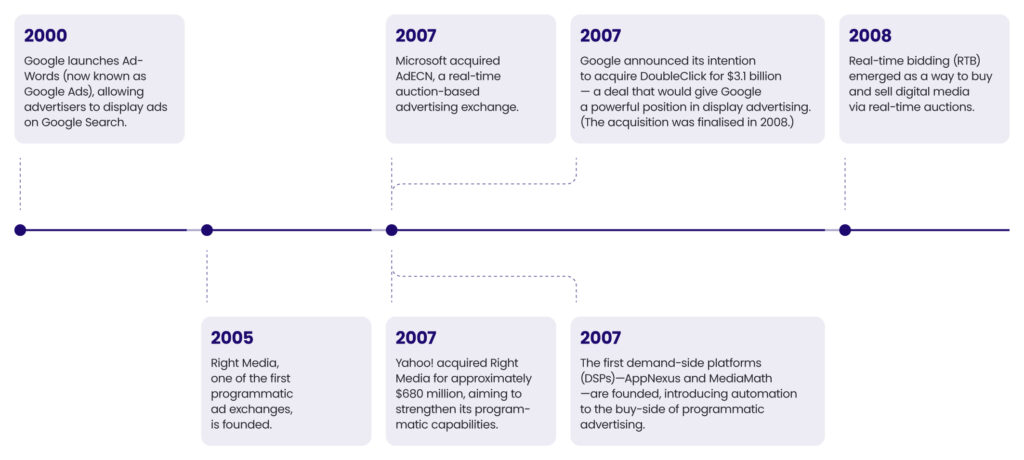

2000 to 2009: The evolution of programmatic advertising and the introduction of real-time bidding (RTB)

By the early 2000s, the internet was experiencing explosive growth.

More people were coming online, and advertisers needed even better ways to target the right users at the right time.

The limitations of ad networks became apparent—they lacked precision in targeting and didn’t offer real-time pricing based on demand.

This demand for a more automated, data-driven approach led to the introduction of real-time bidding (RTB)—a system where ad inventory could be bought and sold in real time using algorithms and automated bidding.

Three key types of platforms emerged during this transition:

- Demand-side platforms (DSPs) – Allowed advertisers to bid on individual impressions in real-time, using audience data to make data-driven buying decisions.

- Supply-side platforms (SSPs) – Helped publishers manage their inventory dynamically, ensuring that each impression was sold to the highest bidder rather than at pre-negotiated, static rates.

- Ad exchanges – Acted as marketplaces that connected DSPs and SSPs, enabling real-time transactions and allowing advertisers to bid on specific impressions rather than bulk inventory.

DoubleClick’s acquisition of NetGravity in 1999 helped lay the groundwork for one of the first major ad exchanges.

But it wasn’t until the mid-to-late 2000s that real-time bidding (RTB) gained traction, allowing advertisers to purchase ad space on a per-impression basis, in milliseconds.This shift revolutionised digital advertising, giving advertisers:

- More control, as they could decide exactly which impressions to bid on,

- Better targeting, as ads could be tailored to users based on browsing behaviour, demographics, and interests,

- Optimised spending – they no longer had to waste budget on bulk buys that included irrelevant audiences.

At the same time, publishers benefited from increased competition, as multiple advertisers bid against each other in real-time, ensuring higher CPMs (cost per thousand impressions) and better yield optimisation.

The rise of full-stack AdTech platforms

As programmatic advertising took hold, companies expanded their AdTech offerings, creating full-stack solutions that combined multiple technologies into one ecosystem.

This period saw several major acquisitions that shaped the AdTech landscape:

- Yahoo acquired Right Media in 2007, building its own ad exchange business that would later compete with Google.

- Google acquired DoubleClick in 2008 for $3.1 billion, integrating its technology into what would become the Google Ad Exchange (AdX) and Google Ads (formerly AdWords).

- Microsoft entered the space by acquiring AdECN for reportedly $50m-$75m in 2007, though it struggled to gain market share.

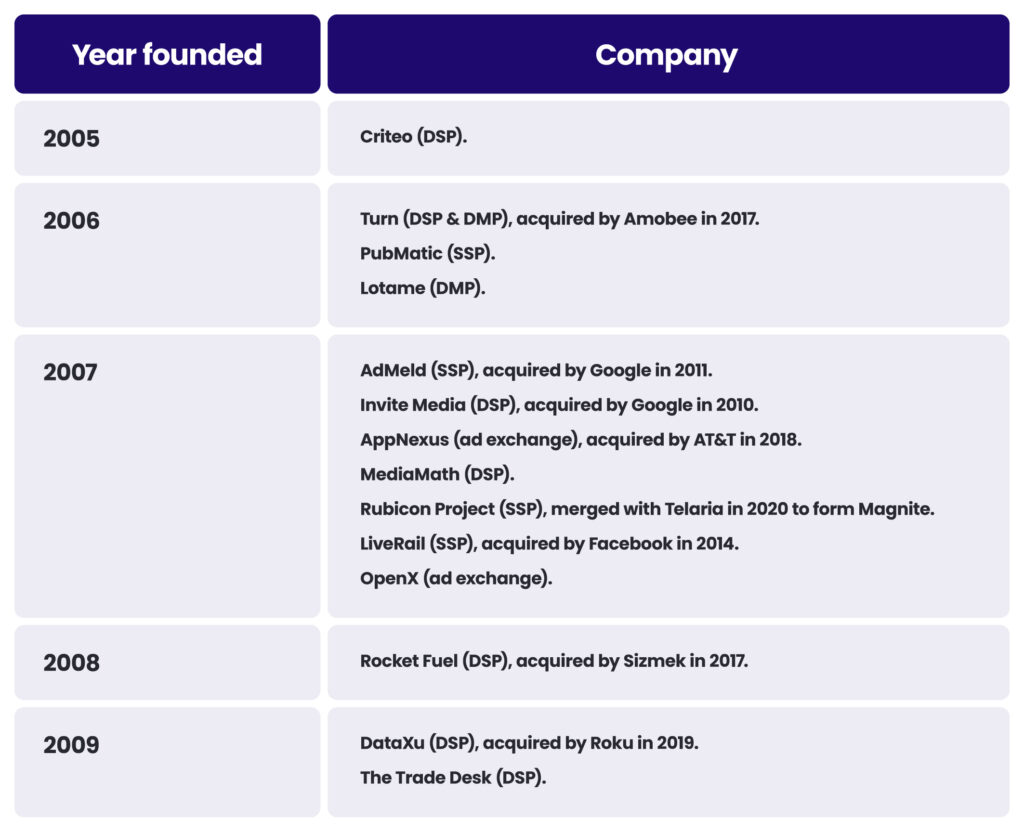

But it wasn’t just the tech giants that were getting into AdTech. Many independent companies were founded to capitalise on the new opportunities offered by the evolution of programmatic advertising.

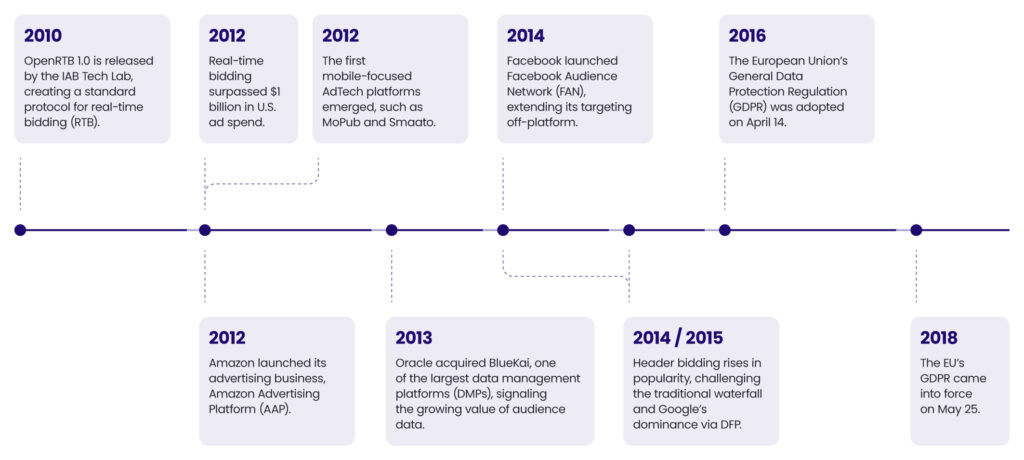

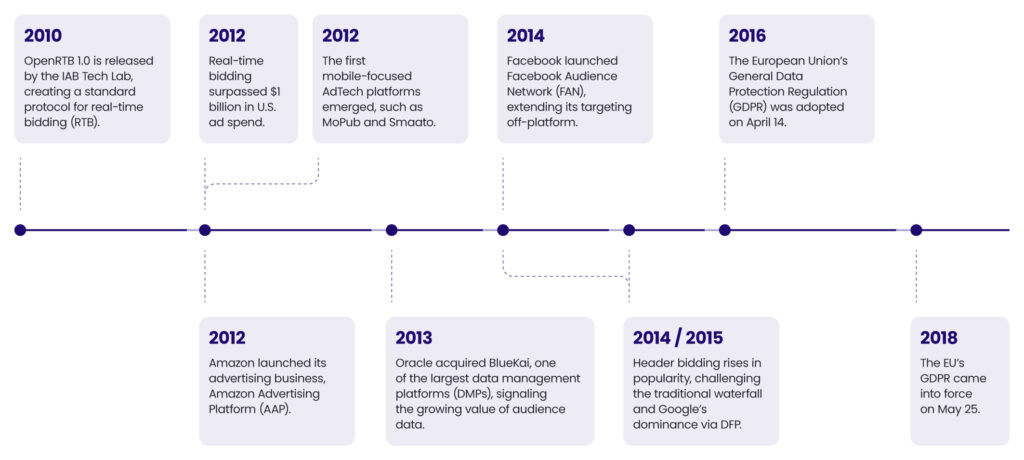

2010 to 2019: The rise of mobile advertising, data, and privacy

By 2010, programmatic advertising dominated display advertising, and new developments—such as dynamic creative optimisation (DCO), AI-driven bidding, and data management platforms (DMPs)—further refined how ads were personalised, measured, and optimised.

AdTech was no longer just a niche industry—it was becoming a fundamental part of the internet economy.

The impact wasn’t just felt by advertisers. Publishers, too, benefited from higher competition for ad space, better pricing control, and improved monetisation strategies.

But with great power came new challenges.

The introduction of data management platforms (DMPs) led to privacy concerns, the increase in ad spend resulted in a rise in ad fraud, and the introduction of more AdTech platforms increased complexity in the ecosystem.

Below are the key themes in programmatic advertising and AdTech between 2010 and 2019.

The rise of mobile advertising

When the iPhone was released in 2007, it not only marked the beginning of the smartphone era but also represented the birth of a new digital advertising channel – mobile advertising.

As mobile devices quickly became the primary way people accessed the internet, advertisers saw an opportunity to reach users in a new environment.

Early mobile ad formats were basic and often adapted from desktop banners, but this rapidly evolved with the introduction of native in-app ads, location-based targeting, and the growth of mobile ad networks like AdMob (acquired by Google in 2009) and Millennial Media.

The launch of the App Store in 2008 and Android Market soon after created massive amounts of new ad inventory, fueling the rise of mobile DSPs and SSPs tailored to in-app environments.

These AdTech platforms adapted by integrating SDKs, mobile-specific formats, and targeting capabilities.

In October 2016, mobile and tablet usage exceeded desktop usage for the first time, representing a significant change in how people access and use internet-power devices. This also marked a change in how advertisers spent their ad budgets with mobile advertising representing 75% of all digital ad spend in 2018.

The introduction of data management platforms (DMPs)

In the early 2010s, as programmatic advertising gained traction, the industry experienced a rapid increase in the volume and complexity of data available to marketers.

This surge led to the rise of data management platforms (DMPs)—centralised systems designed to collect, organise, and activate audience data from various sources, including websites, apps, CRMs, third-party providers, and offline databases.

DMPs enabled advertisers to build more granular audience segments, improve targeting accuracy, and optimise media buying across channels.

Companies like BlueKai (acquired by Oracle in 2014), Lotame, and Neustar played a key role in driving data-driven marketing strategies.

At the same time, the rise of third-party data marketplaces fueled an ecosystem where user behaviour, interests, and demographics were bought and sold at scale and used for ad targeting in RTB auctions.

While DMPs empowered advertisers with unprecedented targeting capabilities, they also contributed to concerns over user privacy, data leakage, and transparency—issues that would later be challenged by regulations such as GDPR and CCPA, and shifts in browser policies around cookies and trackers.

The introduction of standards from the IAB

Between 2010 and 2019, the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) and IAB Tech Lab played a central role in shaping the technical and policy frameworks that underpin the programmatic advertising ecosystem.

As real-time bidding (RTB) and automated buying gained momentum, the IAB introduced a series of standards to promote interoperability, transparency, and trust across platforms.

One of the most foundational milestones was the release of OpenRTB 1.0 in 2010, which standardised how ad exchanges and demand-side platforms communicate during real-time auctions. This was followed by incremental updates—culminating in OpenRTB 2.5 by 2016—that supported rich media, native formats, and device-level data.

To address growing concerns around ad fraud and inventory quality, the IAB Tech Lab introduced ads.txt in 2017—a simple but powerful file publishers could host on their domains to declare authorized sellers of their inventory. This was later extended to app-ads.txt for mobile apps and CTV environments.

Video advertising also became a key focus, with updates to the VAST (Video Ad Serving Template) standard, including the release of VAST 4.1 in 2018. This version introduced support for OMID (Open Measurement Interface Definition), a standard that enabled third-party viewability and verification measurement within video environments.

With the introduction of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018, the IAB Tech Lab launched the Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF) in 2018, providing a way for publishers, advertisers, and vendors to manage GDPR-compliant consent signals across the ad supply chain. A more flexible and robust TCF 2.0 followed in 2019.

These standards were critical to the growth and maturation of programmatic advertising—ensuring that diverse platforms could work together, fraud could be mitigated, and user rights could be respected in an increasingly complex digital environment.

The evolution of media-buying processes

The release of OpenRTB 1.0 in 2010 represented a fundamental transformation in programmatic advertising.

Initially, programmatic buying relied heavily on open auctions, where advertisers bid in real time for individual ad impressions based on user and contextual signals.

This shift to RTB introduced unprecedented speed, efficiency, and targeting precision—but also raised concerns about brand safety, transparency, and data leakage.

In response, private marketplaces (PMPs) emerged, allowing advertisers to access premium inventory through automated workflows while preserving some of the control and exclusivity of traditional media buying.

The introduction and rapid adoption of header bidding around 2015 marked another major shift.

This technique allowed publishers to offer inventory simultaneously to multiple exchanges, bypassing the “waterfall” hierarchy that had long favored Google’s ad stack and improving yield across the board.

By the end of the decade, server-side header bidding and supply-path optimisation (SPO) strategies further streamlined the buying process and reduced inefficiencies.

By the end of the 2010s, advancements in machine learning and AI had brought a new level of automation to media buying.

Bidding strategies, budget pacing, audience segmentation, and even creative selection became algorithmically driven, reducing the need for manual campaign management and enabling real-time optimisation at scale.

The rise of privacy regulations and policies changes

Between 2010 and 2019, privacy and data protection became defining themes in the evolution of programmatic advertising.

As the ecosystem matured and reliance on user-level data intensified, growing public awareness and regulatory scrutiny led to significant changes in how data could be collected, shared, and used across the digital advertising supply chain.

Early in the decade, most user tracking and targeting relied on third-party cookies, mobile ad IDs (like Apple’s IDFA and Google’s AAID), and widespread data sharing among platforms.

However, concerns about consumer privacy, lack of transparency, and data leakage began to mount—prompted by revelations about opaque data practices and the emergence of large-scale behavioural profiling.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), adopted in 2016 and enforced from May 25, 2018, was a watershed moment. It imposed strict requirements on data collection, usage, and user consent for any organisation processing personal data of EU residents.

GDPR forced AdTech companies to overhaul how they handled consent, data sharing, and user identification, with many adopting consent management platforms (CMPs) and limiting reliance on third-party data sources.

Meanwhile, browser developers began implementing their own privacy safeguards.

Apple’s Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP), launched in 2017 in Safari, restricted the lifespan of third-party cookies and limited cross-site tracking. Mozilla’s Firefox followed with Enhanced Tracking Protection (ETP), and Google signaled a shift in its own approach by announcing plans to improve Chrome’s privacy controls and explore alternatives to cookies.

By the end of 2019, it was clear that privacy would not be a temporary challenge but a permanent, strategic concern.

Advertisers, publishers, and platforms began investing heavily in first-party data strategies, data clean rooms, identity solutions, and privacy-preserving technologies in anticipation of a more regulated and consent-driven advertising future.

The history of AdTech and programmatic advertising at a glance

Digital advertising has undergone a step-by-step transformation, driven by the need for better efficiency, targeting, automation, and measurement.

Each major innovation in AdTech has emerged as a direct response to an inefficiency in the previous system, setting the foundation for the next technological leap.

2020 and beyond: The future of AdTech

AdTech has undergone rapid evolution over the past two decades, transitioning from manual ad placements to real-time bidding (RTB), programmatic automation, and AI-driven optimisation.

As we look ahead to programmatic advertising’s third decade, fundamental shifts in privacy, data usage, AI, and ecosystem consolidation will shape the industry’s trajectory.

With third-party cookies now gone from Firefox and Safari, AI accelerating automation, and regulatory scrutiny increasing, the digital advertising landscape is poised for significant transformation.

Companies that adapt to privacy-first advertising, embrace AI-driven automation, and build first-party data strategies will gain a competitive edge, while those that fail to innovate risk becoming obsolete.

A summary of key milestones in AdTech

Next chapter

Chapter 02: The AdTech & Programmatic Advertising Landscape

Download the PDF & join our waiting list

Fill in the form to download the PDF version and get notified when the next chapters are released.